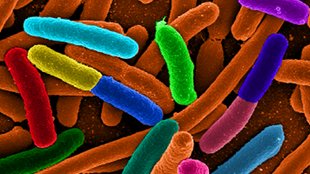

WIKIMEDIA, MATTOSAURUSSurgically bypassing the stomach is not the only reason that patients undergoing such a procedure quickly begin to drop pounds. Changes to the microbial make-up of their intestines also play a big role, according to a paper published in Science Translational Medicine today (March 27). The results suggest that tweaking a person’s gut microbes to mimic the effects of bypass treatment might, one day, be an effective means of losing weight without the need for surgery.

WIKIMEDIA, MATTOSAURUSSurgically bypassing the stomach is not the only reason that patients undergoing such a procedure quickly begin to drop pounds. Changes to the microbial make-up of their intestines also play a big role, according to a paper published in Science Translational Medicine today (March 27). The results suggest that tweaking a person’s gut microbes to mimic the effects of bypass treatment might, one day, be an effective means of losing weight without the need for surgery.

“What they’ve shown in this paper is that gastric bypass has an effect on the bacteria of the intestine, and that if you take those bacteria and transplant them into another mouse [that hasn’t had surgery] . . . that mouse [also] loses weight, which is amazing,” said Louis Aronne, a professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, who was not involved in the study.

Obesity can be accompanied by an array of life-threatening complications such as diabetes and heart disease. But, as many people will attest to, losing weight can be a real struggle.

The problem with regular dieting is that “when you are forced to eat less . . . your body reacts by reducing basal energy expenditure,” said ...