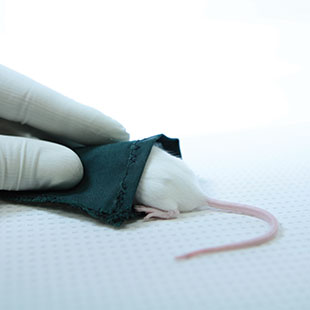

STRESS REDUCER: Picking up mice can be the most stressful part of a test for the rodents and for researchers trying to avoid nips. “Mouse havens” let the animal hide and feel safe, while making transport between the testing apparatus and cage easy.JEAN-SEBASTIEN AUSTINMice and rats account for 95 percent of the vertebrates used in research. Mice occupy the preferred spot, largely due to our ever-improving ability to manipulate their genetics, as well as to their smaller size, superb breeding abilities, and docility. These animals are vital for work that cannot be done on humans, including investigating the brain’s complex functions, diseases, and disorders. Researchers have fine-tuned ways to screen for genetic glitches, measure hormone levels, and watch neurons fire, among countless other physiological processes. But studying mouse behavior remains something of a dark art.

STRESS REDUCER: Picking up mice can be the most stressful part of a test for the rodents and for researchers trying to avoid nips. “Mouse havens” let the animal hide and feel safe, while making transport between the testing apparatus and cage easy.JEAN-SEBASTIEN AUSTINMice and rats account for 95 percent of the vertebrates used in research. Mice occupy the preferred spot, largely due to our ever-improving ability to manipulate their genetics, as well as to their smaller size, superb breeding abilities, and docility. These animals are vital for work that cannot be done on humans, including investigating the brain’s complex functions, diseases, and disorders. Researchers have fine-tuned ways to screen for genetic glitches, measure hormone levels, and watch neurons fire, among countless other physiological processes. But studying mouse behavior remains something of a dark art.

For one thing, mice—a prey species—are easily stressed. Earlier this year, Jeffery Mogil, a professor of behavioral neuroscience and a pain researcher at McGill University, and his colleagues confirmed a lab legend when they reported that the presence of male experimenters sends the animals’ cortisol levels soaring (Nat Methods, 11:629-32, 2014). Stress-hormone elevation can affect not just pain assays but other behavioral tests, as well as cells and tissue harvested for nonbehavioral experiments. But that isn’t the only hidden variable that can cause experimental differences. “The lab environment is most certainly filled with confounding factors,” Mogil says. “And we’ve been failing to take them seriously.” Then there are the tests themselves, which can be tricky to perform and interpret. Ultimately, testing behaviors in mice is ...