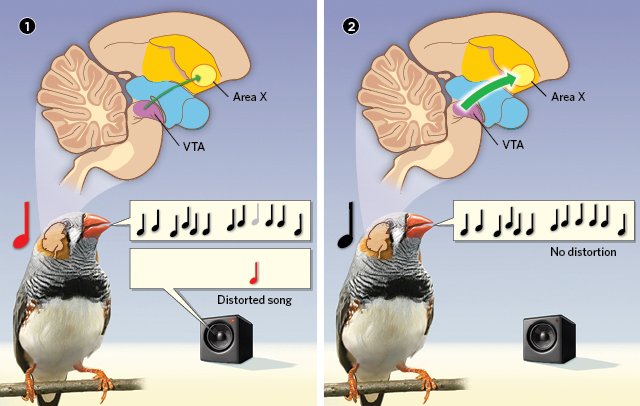

NEGATIVE FEEDBACK: In the brain of male zebra finches, dopaminergic neurons (green arrows) project from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to Area X, a region known to be required for song learning. Researchers from Cornell University found that these neurons encode singing errors by suppressing dopamine signaling when the bird hears itself producing an incorrect note, which researchers simulated by the introduction of distorted audio feedback at specific syllables (1)—and boosting dopamine signaling when the bird correctly produces a note that sounded incorrect in previous attempts (2).© PENS AND BEETLES STUDIOS

NEGATIVE FEEDBACK: In the brain of male zebra finches, dopaminergic neurons (green arrows) project from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to Area X, a region known to be required for song learning. Researchers from Cornell University found that these neurons encode singing errors by suppressing dopamine signaling when the bird hears itself producing an incorrect note, which researchers simulated by the introduction of distorted audio feedback at specific syllables (1)—and boosting dopamine signaling when the bird correctly produces a note that sounded incorrect in previous attempts (2).© PENS AND BEETLES STUDIOS

The paper

V. Gadagkar et al., “Dopamine neurons encode performance error in singing birds,” Science, 354:1278-82, 2016.

Recognizing when you’re singing the right notes is a crucial skill for learning a melody, whether you’re a human practicing an aria or a bird rehearsing a courtship song. But just how the brain executes this sort of trial-and-error learning, which involves comparing performances to an internal template, is still something of a mystery. “It’s been an important question in the field for a long time,” says Vikram Gadagkar, a postdoctoral neurobiologist in Jesse Goldberg’s lab at Cornell University. “But nobody’s been able to find out how this actually happens.”

Gadagkar suspected, as others had hypothesized, that internally driven learning might rely on neural mechanisms similar to traditional ...