FLICKR, NICHDConsuming calorie-dense foods usually induces a feeling of satiety in animals. But in humans, large amounts of alcohol—the second most calorie-dense nutrient after fat—can trigger overeating. Now, researchers have found that, in mice, this effect is induced because alcohol activates a specific set of hypothalamic neurons associated with feeding behavior. The results, published today (January 10) in Nature Communications, reveal a previously unrecognized link between binge drinking and binge eating.

FLICKR, NICHDConsuming calorie-dense foods usually induces a feeling of satiety in animals. But in humans, large amounts of alcohol—the second most calorie-dense nutrient after fat—can trigger overeating. Now, researchers have found that, in mice, this effect is induced because alcohol activates a specific set of hypothalamic neurons associated with feeding behavior. The results, published today (January 10) in Nature Communications, reveal a previously unrecognized link between binge drinking and binge eating.

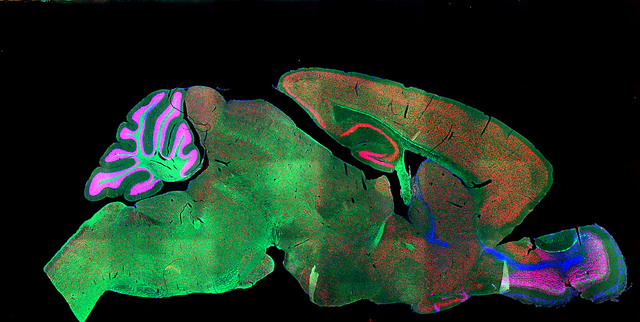

Earlier studies have established that stimulating agouti-related protein (AgRP) neurons, found in the hypothalamuses of mice and humans, is sufficient to cause overeating even when the animal does not need additional energy. Sarah Cains of University College London and colleagues set out to test whether alcohol-induced overeating was mediated by AgRP neurons in mice.

“We were thinking about how alcohol is associated with eating in cultural situations in humans, and wanted to see if there’s something neurological underlying that behavior,” Cains told The Scientist. “So far, it’s only been an association—we didn’t know of a biological explanation for what could trigger eating in the presence of alcohol.”

To begin, the team tested whether alcohol drove mice to binge eat. In an “alcoholic weekend” experiment, the ...