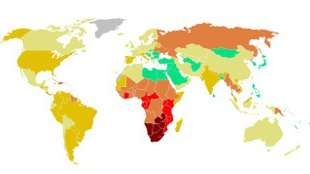

WIKIMEDIA, UNAIDS

WIKIMEDIA, UNAIDS

With the right drugs given at the right time, we can prevent HIV from being passed from mother to child. Despite this technological breakthrough, established in the mid-1990s, some HIV-positive women are being denied access to this potentially life-saving treatment for their infants. And it’s not due to a lack of money or healthcare coverage; it’s the result of a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-supported clinical study that is withholding such treatments for the sake of having a control group.

It’s reminiscent of a dark period in American medical history: the Tuskegee study. Conducted from 1932 to 1976, African American men in Alabama were denied therapy for syphilis with the rationale that the participants wouldn’t have access to therapy anyway. During the past decade, similar ...