WIKIMEDIA, GEORGE WHARTON JAMESFor having a title that invokes the impersonal, black-and-white machinery of bureaucracy, “Informed Consent” brims with color and life. The one-act play by Deborah Zoe Laufer deconstructs the concept of race with the help of a gregarious, diverse cast of characters. It also deconstructs life itself—both into the basic constituents of DNA, and into the stories we tell ourselves in order to survive.

WIKIMEDIA, GEORGE WHARTON JAMESFor having a title that invokes the impersonal, black-and-white machinery of bureaucracy, “Informed Consent” brims with color and life. The one-act play by Deborah Zoe Laufer deconstructs the concept of race with the help of a gregarious, diverse cast of characters. It also deconstructs life itself—both into the basic constituents of DNA, and into the stories we tell ourselves in order to survive.

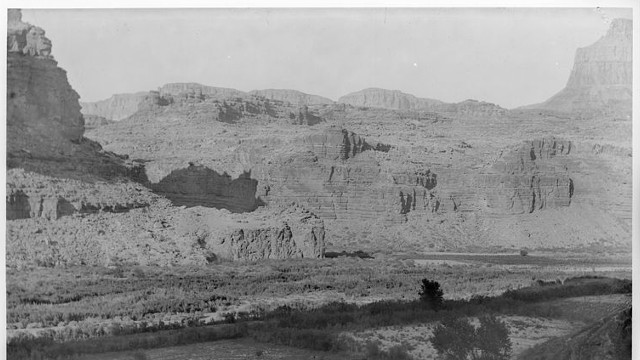

The place where revered stories cannot be reconciled with hard facts is the battleground where the play’s conflicts take place. Jillian (Tina Benko), the play’s hard-nosed protagonist, is a genetic anthropologist whose zeal for the scientific process approaches— perhaps even surpasses—religious fervor. Her passion, and her stubborn unwillingness to truly respect alternative points of view, bring her into conflict with virtually every other major character, most notably Arella (Delanna Studi), a Native American woman who represents an indigenous tribe that resides in the Grand Canyon.

After generations of depredations at the hands of so-called pioneers and the U.S. government, Arella’s once-proud tribe is reduced to eating nutrient-poor, government-issue food, and suffers from a high rate of diabetes. Jillian is assigned to investigate the genetic anthropology ...