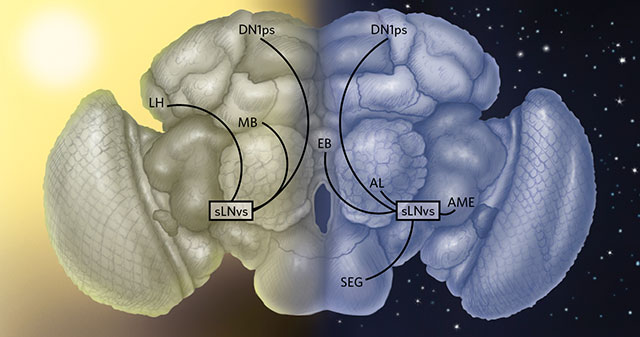

TIMED CONNECTIONS: Circadian neurons in Drosophila brains reveal considerable plasticity, breaking and creating connections with different parts of the brain over the course of a day. For instance, during the day, one group of circadian neurons known as sLNvs connects with other circadian cells called DN1ps and with noncircadian cells of the mushroom body (MB) and lateral horn (LH). At night, sLNv neurons maintain contact with DN1ps, but also connect with neurons in the ellipsoid body (EB), the subesophagic ganglion (SEG), antennal lobes (AL), and accessory medulla (AME), while losing contact with some daytime partners.© LAURIE O'KEEFE

TIMED CONNECTIONS: Circadian neurons in Drosophila brains reveal considerable plasticity, breaking and creating connections with different parts of the brain over the course of a day. For instance, during the day, one group of circadian neurons known as sLNvs connects with other circadian cells called DN1ps and with noncircadian cells of the mushroom body (MB) and lateral horn (LH). At night, sLNv neurons maintain contact with DN1ps, but also connect with neurons in the ellipsoid body (EB), the subesophagic ganglion (SEG), antennal lobes (AL), and accessory medulla (AME), while losing contact with some daytime partners.© LAURIE O'KEEFE

The paper

E.A. Gorostiza et al., “Circadian pacemaker neurons change synaptic contacts across the day,” Current Biology, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.063, 2014.

Stripped of smartphones, watches, or a few days of sunshine, most animals’ bodies still follow an inner biological clock to demarcate day from night. This circadian rhythm dictates when we wake and sleep; it also controls the time of day when neurons are most likely to learn, remember, and perform other crucial functions.

In Drosophila, this biological clock comprises 150–200 neurons nestled in seven clusters that include the small ventral lateral (sLNv) neurons. Researchers had known that these circadian pacemakers keep fly brains on a clock by rhythmically releasing chemical cues such as pigment dispensing factor (PDF) and other neurotransmitters. But in a 2008 study, María ...