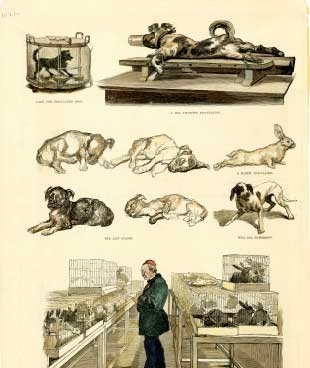

SHROUDED IN SECRECY: Pasteur initially believed that a vaccine had to be live in order to confer immunity. The method he claimed to have used to treat rabies in test subject Joseph Meister was based on his previous research in rabid dogs and rabbits (like the ones Pasteur is shown examining in this panel from Harper’s Weekly, 1884). This method involved passaging the virus through animals, then desiccating extracted spinal cord tissue for increasing lengths of time in an attempt to reduce its virulence. Meister received a series of injections apparently going from the least to the most virulent spinal cord. But Pasteur’s lab notebooks, released in the 1970s, suggest the concoction may instead have been developed with different methods not yet fully tested in dogs.COURTESY OF THE US NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINEOn July 6, 1885, three men in Paris prepared to treat Joseph Meister, a nine-year-old from Alsace who had been bitten multiple times by a rabid dog. Two of the men were medically trained; the third was the therapy’s creator, a chemist-turned-microbiologist named Louis Pasteur.

SHROUDED IN SECRECY: Pasteur initially believed that a vaccine had to be live in order to confer immunity. The method he claimed to have used to treat rabies in test subject Joseph Meister was based on his previous research in rabid dogs and rabbits (like the ones Pasteur is shown examining in this panel from Harper’s Weekly, 1884). This method involved passaging the virus through animals, then desiccating extracted spinal cord tissue for increasing lengths of time in an attempt to reduce its virulence. Meister received a series of injections apparently going from the least to the most virulent spinal cord. But Pasteur’s lab notebooks, released in the 1970s, suggest the concoction may instead have been developed with different methods not yet fully tested in dogs.COURTESY OF THE US NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINEOn July 6, 1885, three men in Paris prepared to treat Joseph Meister, a nine-year-old from Alsace who had been bitten multiple times by a rabid dog. Two of the men were medically trained; the third was the therapy’s creator, a chemist-turned-microbiologist named Louis Pasteur.

Despite being relatively rare, rabies (or hydrophobia, as it was also known) commanded a fearful fascination in Europe; wildly foaming at the mouth, its victims died painfully and dramatically. But the virus’s incubation period also made rabies of interest to Pasteur—already a famous scientist in France—as a candidate for a new type of vaccine.

“The time from the bite to the sickness was pretty long, usually around a month or longer,” explains Kendall Smith, an immunologist at Weill Cornell Medical College. “There would be time to intervene with a therapeutic vaccine.”

By 1885, five years after starting work on rabies, Pasteur and his colleagues had developed a live viral preparation, which, Pasteur claimed, not only protected dogs from rabies infections, but prevented the disease from ...