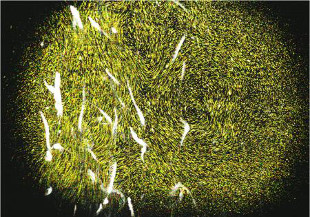

Migrating brine shrimp (white) generate swirling eddies, as visualized with a high-speed camera using microscopic tracer particles (yellow). CALTECH, MONICA WILHELMUS AND JOHN DABIRI

Migrating brine shrimp (white) generate swirling eddies, as visualized with a high-speed camera using microscopic tracer particles (yellow). CALTECH, MONICA WILHELMUS AND JOHN DABIRI

Diminutive drifting animals such as krill and copepods make up a large proportion of the biomass in the world’s oceans, but their effects on ocean circulation patterns are not well understood. A laboratory study of brine shrimp revealed that their swimming could add as much energy to ocean water as winds or tides. The findings, reported this week (September 30) in Physics of Fluids, could inform more accurate climate change predictions.

Although brine shrimp typically live in salty lakes, they exhibit daily migration patterns similar to zooplankton in the ocean. At dusk, large groups of animals swim up to the water’s surface, where they feed on smaller photosynthetic plankton and evade predators in the dark. They retreat to deeper waters at sunrise, sometimes traveling hundreds ...