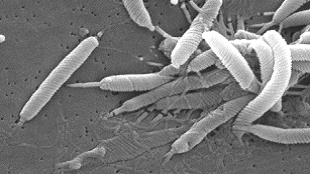

Helicobacter sp.WIKIPEDIA, CDCThe ulcer-causing bacteria Helicobacter pylori swiftly swarm to sites of microscopic damage on the surface of the mouse stomach. The microbes accumulate at these injury sites within minutes, and can slow tissue repair. These are the earliest events in H. pylori pathogenesis reported in vivo, according to a study published today (July 17) in PLOS Pathogens.

Helicobacter sp.WIKIPEDIA, CDCThe ulcer-causing bacteria Helicobacter pylori swiftly swarm to sites of microscopic damage on the surface of the mouse stomach. The microbes accumulate at these injury sites within minutes, and can slow tissue repair. These are the earliest events in H. pylori pathogenesis reported in vivo, according to a study published today (July 17) in PLOS Pathogens.

Previous studies have shown that both motility and chemotaxis are crucial to H. pylori colonization in the stomach. Mutants that are unable to sense pH gradients or concentrations of chemicals such as urea, arginine, or carbon dioxide are less capable of causing ulcers, requiring several times more bacteria than wild-type strains. But how these properties helped the bacteria colonize damaged stomach tissue was not clear.

The present study “is a very nice example of how very basic bacterial properties—such as their abilities to swim or sense where they’re going—can have really important effects in disease,” said microbiologist Manuel Amieva of Stanford University who was not involved with the work. “We sometimes ignore these, because we look for disease-related factors.”

Alcohol, smoking, salt intake, and certain ...