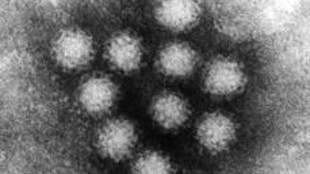

WIKIMEDIA, GLEIBERGLike the human gastrointestinal tract, the mouse gut is home to beneficial bacteria that help boost the host immune system and ward off pathogens, among other things. Wipe out this commensal microbiome, and the mice are more susceptible to intestinal injury and infection. But the presence of murine norovirus (MNV) appears to recover some of these beneficial functions in the guts of germ-free or antibiotic-treated mice, according to a study published in Nature today (November 19).

WIKIMEDIA, GLEIBERGLike the human gastrointestinal tract, the mouse gut is home to beneficial bacteria that help boost the host immune system and ward off pathogens, among other things. Wipe out this commensal microbiome, and the mice are more susceptible to intestinal injury and infection. But the presence of murine norovirus (MNV) appears to recover some of these beneficial functions in the guts of germ-free or antibiotic-treated mice, according to a study published in Nature today (November 19).

Specifically, Ken Cadwell of the Skirball Institute of Biomolecular Medicine at New York University’s Langone Medical Center and his colleagues found that MNV infection in germ-free and antibiotic-treated mice helped repair morphological defects within the intestine related to the lack of bacteria and boosted the production of immune cells and signaling molecules there.

“It’s as if we took these germ-free mice and gave back their [beneficial] bacteria,” Cadwell told reporters during a press briefing today.

“[That] an intestinal virus can have beneficial effects for the host [has] never really been shown before, at least for mammalian viruses,” said Julie Pfeiffer, a microbiologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center who was not involved in the work but coauthored an article accompanying the study. “They’re ...