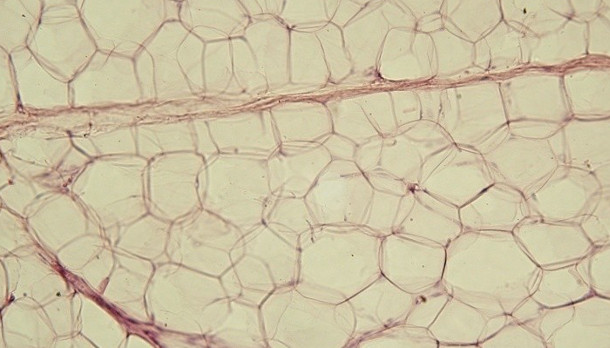

Yellow adipose tissueWIKICOMMONS, JAGIELLONIAN UNIV. MEDICAL COLLEGEDying fat cells in obese mice release cell-free DNA, recruiting immune cells that can drive chronic inflammation and insulin resistance within adipose tissue, according to a study published today (March 25) in Science Advances. The observed accumulation of macrophages in murine fat tissue depended on the expression of Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9). Obese mice missing TLR9 had fewer macrophages and were more insulin sensitive compared to their TLR9-expressing counterparts. The new work may partly explain how obesity can drive chronic inflammation.

Yellow adipose tissueWIKICOMMONS, JAGIELLONIAN UNIV. MEDICAL COLLEGEDying fat cells in obese mice release cell-free DNA, recruiting immune cells that can drive chronic inflammation and insulin resistance within adipose tissue, according to a study published today (March 25) in Science Advances. The observed accumulation of macrophages in murine fat tissue depended on the expression of Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9). Obese mice missing TLR9 had fewer macrophages and were more insulin sensitive compared to their TLR9-expressing counterparts. The new work may partly explain how obesity can drive chronic inflammation.

“Many mechanisms are involved in obesity-related adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance,” study coauthor Daiju Fukuda of University of Tokushima, Japan, wrote in an email to The Scientist. “We think that our result is one of [these mechanisms].”

“This is a very important piece to help explain the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease,” Gokhan Hotamisligil, a professor of genetics and metabolism at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health told The Scientist. “This paper offers a possibility of explaining how inflammation [within fat tissue] starts. Conceptually, this builds on ideas that have been brewing in the field for two decades,” added Hotamisligil, who was not involved in the study.

“This is very novel because, I think, few would have thought to home in on ...