ISTOCK, KINWUN

ISTOCK, KINWUN

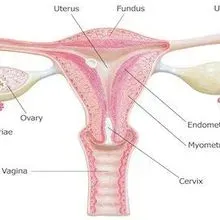

Scientists have long known that in healthy humans, a diverse universe of microbes exists in the vagina. But the existence of bacteria in women’s upper reproductive tract, which includes the uterus and fallopian tubes, remains controversial. A new study, published today (October 17) in Nature Communications, reports that even in the absence of infection, distinct communities of microbes live in these areas.

“The question about whether there are bacteria in the reproductive tract has been on the table for several years at least,” says Larry Forney, a microbiologist at the University of Idaho who was not involved in the work. “I think it’s a pretty strong study, and I think people will take it for what it is, which is a good, initial effort.”

Prior ...