© AMNH/D. FINNINYou enter through a dark corridor studded with points of light—green, red, and blue coming from all directions. The lights represent not stellar glimmers but microbial cells. Mirrors on the walls amplify the spots of brightness, and you see yourself among them. These aren’t just any microbes; they’re the trillions of viruses, fungi, bacteria, and protozoans living in and on your body.

© AMNH/D. FINNINYou enter through a dark corridor studded with points of light—green, red, and blue coming from all directions. The lights represent not stellar glimmers but microbial cells. Mirrors on the walls amplify the spots of brightness, and you see yourself among them. These aren’t just any microbes; they’re the trillions of viruses, fungi, bacteria, and protozoans living in and on your body.

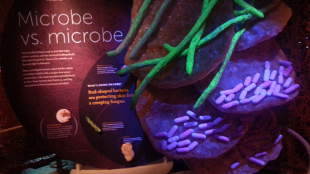

“The Secret World Inside You,” which opens at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) tomorrow (November 7), takes visitors on a tour of the human microbiome—a collection of organisms that weigh 2–3 pounds, or about the same weight as the brain. And like the brain, our commensal microbes influence the way the body works, from digestion to cognition and behavior. “Each of us is a complex ecosystem made of hundreds of species, one of which human and the rest microbial,” show cocurator Robert DeSalle, a scientist in AMNH’s division of invertebrate zoology and the Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics, said in a statement.

ASHLEY P. TAYLOR

ASHLEY P. TAYLOR Digital rendering of Toxoplasma gondii © AMNH

Digital rendering of Toxoplasma gondii © AMNH © AMNH/D. FINNINYou may have heard the story of the parasite that makes mice unafraid of cats. Toxoplasma gondii reproduces in felines and uses mice as a vector to go from cat to cat. We humans, the exhibit explains, are subject to similar microbial influences. People infected with T. gondii have a higher rate of car accidents, for example.

© AMNH/D. FINNINYou may have heard the story of the parasite that makes mice unafraid of cats. Toxoplasma gondii reproduces in felines and uses mice as a vector to go from cat to cat. We humans, the exhibit explains, are subject to similar microbial influences. People infected with T. gondii have a higher rate of car accidents, for example.