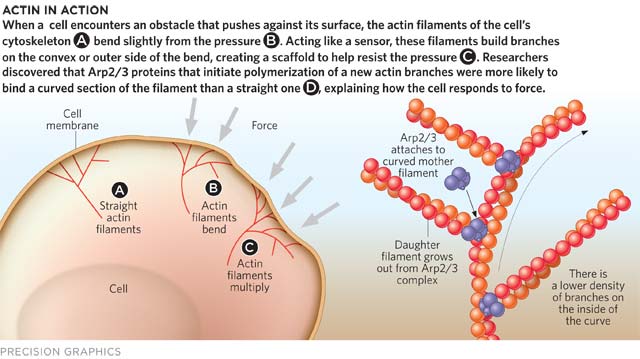

When a cell hits an obstacle, the actin filaments driving the membrane protrusion must reorganize and create additional branches to resist the pressure. Dan Fletcher at the University of California, Berkeley, and colleagues wanted to understand what effect that force has on the branching of actin filaments. They first glued unbranched actin filaments to a surface, some curved, some straight, and then added the raw materials necessary for the branching: the branch-initiating complex Arp2/3, the nucleation-promoting factor that activates it, and raw actin monomers, which polymerize into two tightly wound strands under the right conditions.

The researchers found that new actin branches were more likely to form on the convex side, or outer side, of curved segments. The questions were why and how the branching was occurring mostly on that side, says Fletcher. He recalled early studies on actin in which researchers noticed that isolated filaments would wiggle and ...