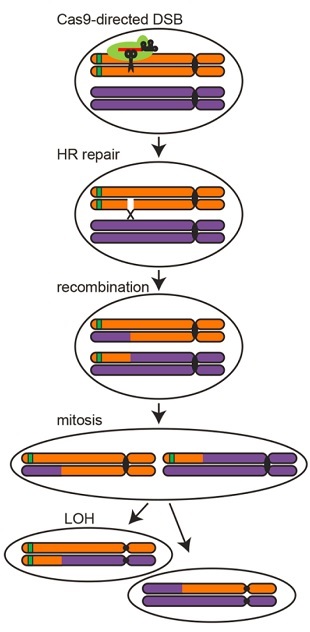

Researchers used CRISPR/Cas9 to make a targeted double-strand break (DSB) in one arm of a yeast chromosome labeled with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene. A within-cell mechanism called homologous repair (HR) mends the broken arm using its homolog, resulting in a recombined region from the site of the break to the chromosome tip. When this cell divides by mitosis, each daughter cell will contain a homozygous section in an outcome known as “loss of heterozygosity” (LOH). One of the daughter cells is detectable because, due to complete loss of the GFP gene, it will no longer be fluorescent.REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM M.J. SADHU ET AL., SCIENCE When mapping phenotypic traits to specific loci, scientists typically rely on the natural recombination of chromosomes during meiotic cell division in order to infer the positions of responsible genes. But recombination events vary with species and chromosome region, giving researchers little control over which areas of the genome are shuffled. Now, a team at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), has found a way around these problems by using CRISPR/Cas9 to direct targeted recombination events during mitotic cell division in yeast. The team described its technique today (May 5) in Science.

Researchers used CRISPR/Cas9 to make a targeted double-strand break (DSB) in one arm of a yeast chromosome labeled with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene. A within-cell mechanism called homologous repair (HR) mends the broken arm using its homolog, resulting in a recombined region from the site of the break to the chromosome tip. When this cell divides by mitosis, each daughter cell will contain a homozygous section in an outcome known as “loss of heterozygosity” (LOH). One of the daughter cells is detectable because, due to complete loss of the GFP gene, it will no longer be fluorescent.REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM M.J. SADHU ET AL., SCIENCE When mapping phenotypic traits to specific loci, scientists typically rely on the natural recombination of chromosomes during meiotic cell division in order to infer the positions of responsible genes. But recombination events vary with species and chromosome region, giving researchers little control over which areas of the genome are shuffled. Now, a team at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), has found a way around these problems by using CRISPR/Cas9 to direct targeted recombination events during mitotic cell division in yeast. The team described its technique today (May 5) in Science.

“Current methods rely on events that happen naturally during meiosis,” explained study coauthor Leonid Kruglyak of UCLA. “Whatever rate those events occur at, you’re kind of stuck with. Our idea was that using CRISPR, we can generate those events at will, exactly where we want them, in large numbers, and in a way that’s easy for us to pull out the cells in which they happened.”

Generally, researchers use coinheritance of a trait of interest with specific genetic markers—whose positions are known—to figure out what part of the genome is responsible for a given phenotype. But the procedure often requires impractically large numbers of progeny or generations to observe the few cases in which coinheritance happens to be disrupted informatively. What’s more, the resolution of ...