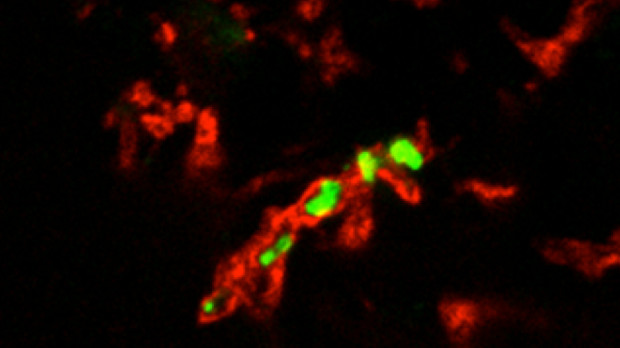

H. ducreyi (green) surrounded by human fibrinogen (red) from a pustule biopsy MARGARET BAUER, INDIANA UNIVERSITYTo understand whether the human skin microbiome can affect the ability of a bacterial pathogen to cause an infection, researchers have had to rely on observational studies. Now, taking advantage of a unique human skin infection model, Stanley Spinola of Indiana University and his colleagues, have found evidence to suggest that the makeup of the skin microbiome plays a role in whether an individual can clear a certain bacterial infection without intervention. The results, published this week (September 15) in mBio, provide another example of how the ecology of human skin can influence health and disease.

H. ducreyi (green) surrounded by human fibrinogen (red) from a pustule biopsy MARGARET BAUER, INDIANA UNIVERSITYTo understand whether the human skin microbiome can affect the ability of a bacterial pathogen to cause an infection, researchers have had to rely on observational studies. Now, taking advantage of a unique human skin infection model, Stanley Spinola of Indiana University and his colleagues, have found evidence to suggest that the makeup of the skin microbiome plays a role in whether an individual can clear a certain bacterial infection without intervention. The results, published this week (September 15) in mBio, provide another example of how the ecology of human skin can influence health and disease.

“The [authors] took advantage of a very clean system—human volunteer inoculation,” said microbiologist Martin Blaser of the New York University Langone Medical Center who was not involved in the study. “We have a paper of the same idea, but this study is better. We had asked whether the [skin] microbiota could predict who would get a [Staphylococcus] bacterial skin infection and who wouldn’t. But our system was based on emergency room samples and had a lot of heterogeneity because we were doing an observational study.”

“This is an interesting report, and most important, because it takes yet another step toward seeking evidence of a clear function of the microbiome,” Richard Gallo, chief of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine, who ...