© SILVIA OTTE/GETTY IMAGES

© SILVIA OTTE/GETTY IMAGES

James Black, a 62-year-old London taxi cab driver, went to his doctor complaining of memory difficulties and intermittent periods of confusion that he’d been experiencing for 2 years. A minor road accident caused by poor concentration and vision problems had forced him to retire. His wife reported that for more than a decade James had also experienced difficulty smelling—a condition, called hyposmia, that was confirmed by olfactory testing. His neurological examination revealed he was suffering from damage to the brain’s frontal lobe. Ultimately, James was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common dementia-causing disorder.1

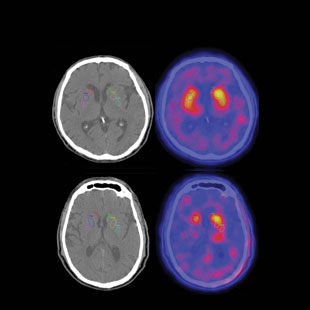

OLFACTORY DIAGNOSIS: Patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD; bottom row) have fewer dopamine tranporters (labeled with radioactive ligands in brain scans on right) than healthy controls (top row). Because PD patients have associated olfactory loss, smell testing can help diagnosticians differentiate between PD and other neurodegenerative diseases that also show a decline in brain dopamine receptors. COURTESY OF JACOB DUBROFFJames’s situation is far from unique. Olfactory loss is not only an early warning sign of AD, but also of Parkinson’s disease (PD) and some other neurological disorders, presenting long before their classic clinical symptoms. Once such symptoms become evident, evaluation of olfactory ability—which is easily performed using commercially available smell tests—can help ensure the correct diagnosis and treatment strategy. Indeed, a number of diseases often misdiagnosed as AD or PD, such as severe depression or progressive supranuclear palsy, are accompanied by little or no smell loss. Thus, olfactory testing can be useful in differentiating between such oft-confused disorders.

OLFACTORY DIAGNOSIS: Patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD; bottom row) have fewer dopamine tranporters (labeled with radioactive ligands in brain scans on right) than healthy controls (top row). Because PD patients have associated olfactory loss, smell testing can help diagnosticians differentiate between PD and other neurodegenerative diseases that also show a decline in brain dopamine receptors. COURTESY OF JACOB DUBROFFJames’s situation is far from unique. Olfactory loss is not only an early warning sign of AD, but also of Parkinson’s disease (PD) and some other neurological disorders, presenting long before their classic clinical symptoms. Once such symptoms become evident, evaluation of olfactory ability—which is easily performed using commercially available smell tests—can help ensure the correct diagnosis and treatment strategy. Indeed, a number of diseases often misdiagnosed as AD or PD, such as severe depression or progressive supranuclear palsy, are accompanied by little or no smell loss. Thus, olfactory testing can be useful in differentiating between such oft-confused disorders.

Importantly, some disorders commonly misdiagnosed ...