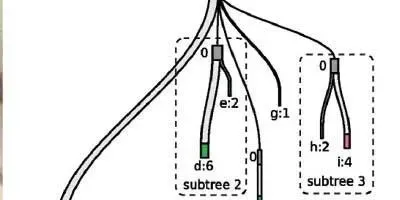

TREE GROWING: BitPhylogeny created this clonal tree from the exome sequences of 58 blood cancer cells. Each node of the tree is a clone (a–i) and the numbers indicate how many cells are in that clone. Certain clones, with 0 cells, were inferred from the data to have existed.K. YUAN ET AL., GENOME BIOL, 16:36, 2015 By the time a person arrives at the doctor’s office with a tumor, a lot has already happened at the cellular—and genomic—level. That cancer sprang from one mutant cell that spawned a mass of cells with additional nucleotide changes and diverse phenotypes.

TREE GROWING: BitPhylogeny created this clonal tree from the exome sequences of 58 blood cancer cells. Each node of the tree is a clone (a–i) and the numbers indicate how many cells are in that clone. Certain clones, with 0 cells, were inferred from the data to have existed.K. YUAN ET AL., GENOME BIOL, 16:36, 2015 By the time a person arrives at the doctor’s office with a tumor, a lot has already happened at the cellular—and genomic—level. That cancer sprang from one mutant cell that spawned a mass of cells with additional nucleotide changes and diverse phenotypes.

To understand the evolutionary history of a cancer, scientists are turning to single-cell sequencing. Conceptually, building a tumor’s family tree is fairly simple: “Cells that have mutation A come before cells that have mutation A and mutation B,” explains Aaron Diaz, a glioblastoma researcher at the University of California, San Francisco. Of course, most tumors are a bit more complicated than just two mutations. From the sequences of dozens of individual cells from the same tumor, computational algorithms build their best guess at how a person’s cancer evolved. This gives researchers an idea of what mutations happened early versus late, how cells might have evolved drug resistance or the ability to metastasize, and what treatments might work best.

Each tumor will yield its own unique ...