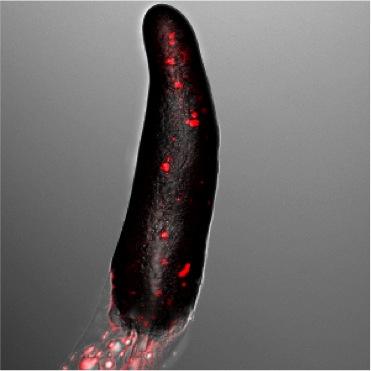

A social amoeba slug. In red are the reactive oxygen species produced by the sentinel cells, which are necessary for the generation of DNA-based nets that defend against bacterial invaders.©THIERRY SOLDATI, UNIGEWhen resources get low, social amoebae Dictyostelium discoideum come together by the thousands to form a stalk topped by a mass of spores, which can blow off in the wind to more-plentiful environments. About 80 percent of the amoebae that contribute to this cooperative structure become spores; approximately 20 percent form the stalk, sacrificing their own survival and reproduction for the success of the group. But there is also a third set of cells—about 1 percent of the population—that maintain the amoeba’s typical phagocytic functions, according to a study published yesterday (March 1) in Nature Communications.

A social amoeba slug. In red are the reactive oxygen species produced by the sentinel cells, which are necessary for the generation of DNA-based nets that defend against bacterial invaders.©THIERRY SOLDATI, UNIGEWhen resources get low, social amoebae Dictyostelium discoideum come together by the thousands to form a stalk topped by a mass of spores, which can blow off in the wind to more-plentiful environments. About 80 percent of the amoebae that contribute to this cooperative structure become spores; approximately 20 percent form the stalk, sacrificing their own survival and reproduction for the success of the group. But there is also a third set of cells—about 1 percent of the population—that maintain the amoeba’s typical phagocytic functions, according to a study published yesterday (March 1) in Nature Communications.

“This last percentage is made up of cells called sentinel cells,” study coauthor Thierry Soldati of the University of Geneva in Switzerland said in a press release. “They make up the primitive innate immune system of the slug and play the same role as immune cells in animals. Indeed, they also use phagocytosis and DNA nets to exterminate bacteria that would jeopardize the survival of the slug.”

Phagocytes of the human innate immune system can kill bacteria by enveloping the foreign bodies and attacking them with reactive oxygen species, or by expelling their own DNA as a poisonous net called a neutrophil extracellular trap (NET), which captures and kills bacteria in the extracellular environment. Amoebae can similarly engulf bacteria in their environment; Soldati and his ...