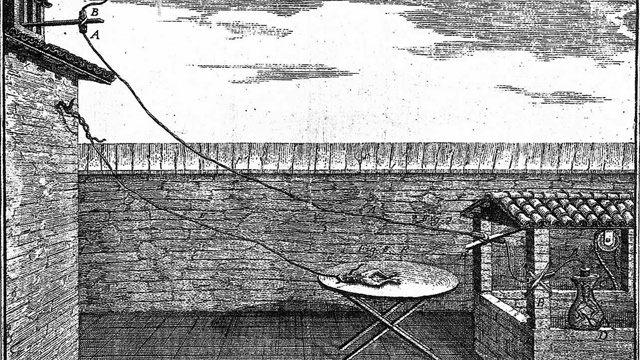

This illustration, from Galvani’s De Viribus Electricitatis in Motu Musculari, published in 1791, shows the experimental setup Galvani used to study the effect of atmospheric electricity on dead frogs.

This illustration, from Galvani’s De Viribus Electricitatis in Motu Musculari, published in 1791, shows the experimental setup Galvani used to study the effect of atmospheric electricity on dead frogs.

In the mid-1780s, Italian physician Luigi Galvani connected the nerves of a recently dead frog to a long metal wire and pointed it toward the sky during a thunderstorm. With each flash of lightning, the frog’s legs twitched and jumped as if they were alive. It was this macabre scene that would inspire the British novelist Mary Shelley to write her gothic masterpiece, Frankenstein, 20 years after the physician’s 1798 death. But more importantly, through such experiments Galvani proved not only that recently-dead muscle tissue can respond to external electrical stimuli, but that muscle and nerve cells possess an intrinsic electrical force responsible for muscle contractions and nerve conduction in living organisms. Galvani named this newly discovered force “animal electricity,” and thus laid foundations for the modern fields of electrophysiology and neuroscience.

Galvani’s contemporaries—including Benjamin Franklin, whose work helped prove the existence of atmospheric electricity—had made great strides in understanding the nature of electricity and how to produce it. Inspired by Galvani’s discoveries, fellow Italian scientist Alessandro Volta would go on to invent, in 1800, the first electrical battery—the voltaic pile—which consisted of brine-soaked pieces of cardboard or cloth sandwiched between disks of different metals. But Volta voiced serious reservations about Galvani’s “animal electricity,” sparking an intense debate that would rage for the last six years of Galvani’s life. Volta believed the source of animal electricity was not intrinsic to the muscle tissue or nerve fibers themselves, as Galvani asserted, but that the animals reacted to electricity produced by two different metals used to connect their nerves ...