More than 15 years ago, Cathy Eng, a medical oncologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, noticed a worrying trend: Cancers typically diagnosed in older adults were increasingly affecting younger individuals. “In my clinic, I was seeing so many young patients with stage four disease,” said Eng. She recalled her youngest patient, a 16-year-old diagnosed with colorectal cancer. “Those kinds of images you don't forget,” said Eng.

Since 1990, the incidence of cancer in individuals aged 50 years and younger, classified as early-onset cancer, has risen globally.1,2 Compared to earlier generations, individuals born in the 1980s (Generation X) and 1990s (Millennials) are increasingly likely to develop certain cancers during their 30s and 40s.3 Since 2011, rates of colorectal cancer (CRC) have been increasing by two percent per year in patients under the age of 50.4 Now, one in five new diagnoses of CRC in the United States are in individuals 54 or younger, up from one in 10 in 1995.5

“Why exactly is this happening? We don't have a good answer at this time,” said Eng.

The rise in early-onset cancers like CRC has puzzled many clinicians and cancer researchers. After all, cancer has been seen as a disease of old age, and over the last few decades, significant progress has been made in reducing the overall incidence of CRC and improving survival rates.6 However, these advancements have been confined to older populations.

Cancer is no longer a disease of older adults, it's become really a disease across the lifespan.

— Andrew Chan, Massachusetts General Hospital

“Cancer is no longer a disease of older adults; it's become really a disease across the lifespan,” said Andrew Chan, a gastroenterologist at Massachusetts General Hospital who specializes in the epidemiology of CRCs.

Although the issue has only recently gained widespread media attention, scientists have been investigating this problem for years, searching for clues to explain the alarming rise. They found several factors, including obesity, lifestyle, and diet, to be associated with an increased risk of early-onset CRC, but their causal roles and underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Moreover, many early-onset CRC patients that Eng and others encountered appeared healthy and had no family history of the disease, suggesting that yet-to-be-identified factors may be at play.

In search of answers, scientists are focusing on how lifelong exposures—ranging from forever chemicals and antibiotics to drastic changes in food production—are driving genetic and biological changes that increase the risk of developing cancers at an earlier age. They hope these insights will inform new prevention strategies and precision medicine approaches that will help the generations most affected by this trend and reverse it for future generations.

Cathy Eng is a medical oncologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, where she treats early-onset colorectal cancer patients.

Cathy Eng

Exposing the Exposome as a Cancer Risk Factor

People from the same birth cohort share more than just their taste in music, sometimes-questionable sense of fashion, and generational slang; they also experience similar societal challenges, food trends, and environmental exposures that influence their early development, health, and life trajectories. The totality of these experiences and exposures over an individual's lifetime, from the prenatal period through adulthood, is referred to as the exposome, and it is increasingly recognized for its importance in shaping disease risk, from diabetes and autoimmune disorders to cancer.

Over the years, scientists have compiled a laundry list of “usual suspects” linked to increased CRC risk: smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and a sedentary lifestyle, to name a few.7,8 Many, if not all, of the risk factors for late-onset CRC are also risk factors for early-onset CRC.9,10 Therefore, generational shifts in the timing and duration of exposures may be a key differentiator between the two populations. “Some of the traditional risk factors that we have observed for colorectal cancer more broadly seem to be operating at an earlier time point in the life course, which we think does help to drive some of these trends,” said Chan. For example, at the same age, Generation Xers and Millennials tend to have higher rates of obesity than previous generations, leading to an earlier and longer exposure to the health effects of obesity. “We need to think about the overlooked aspects of traditional risk factors—for example, when in the life course is potential exposure to risk factors more relevant—and also are there other ways in which risk factors may particularly affect younger people,” added Chan.

However, these traditional risk factors alone cannot explain the phenomena. “We've also been seeing very clearly that there are many individuals that develop early-onset colorectal cancer that don't seem to have these traditional risk factors,” said Chan. He added, “There are still yet uncharacterized risk factors that need to be looked at.”

While a diet that is high in fats and sugars and low in fiber and other key nutrients has long been considered a risk factor for many diseases, the last several decades have witnessed drastic shifts in food production trends. Ultraprocessed foods became ubiquitous in the 1980s and have been a staple in the diets of many Generation Xers and Millennials since childhood, from hotdogs, potato chips, and sodas to foods perceived as healthier, like some breakfast cereals, packaged breads, and ready meals. Chockfull of emulsifiers, food additives, and other industrial formulations that enhance taste, texture, and durability, ultraprocessed foods have come under fire following growing evidence that their consumption is linked to various adverse health outcomes, including CRC, prompting increased scrutiny from health experts and consumers alike.11,12 Around half of the calories consumed by Americans come from ultraprocessed foods, bringing a sense of urgency to efforts to understand their effects on human health.13

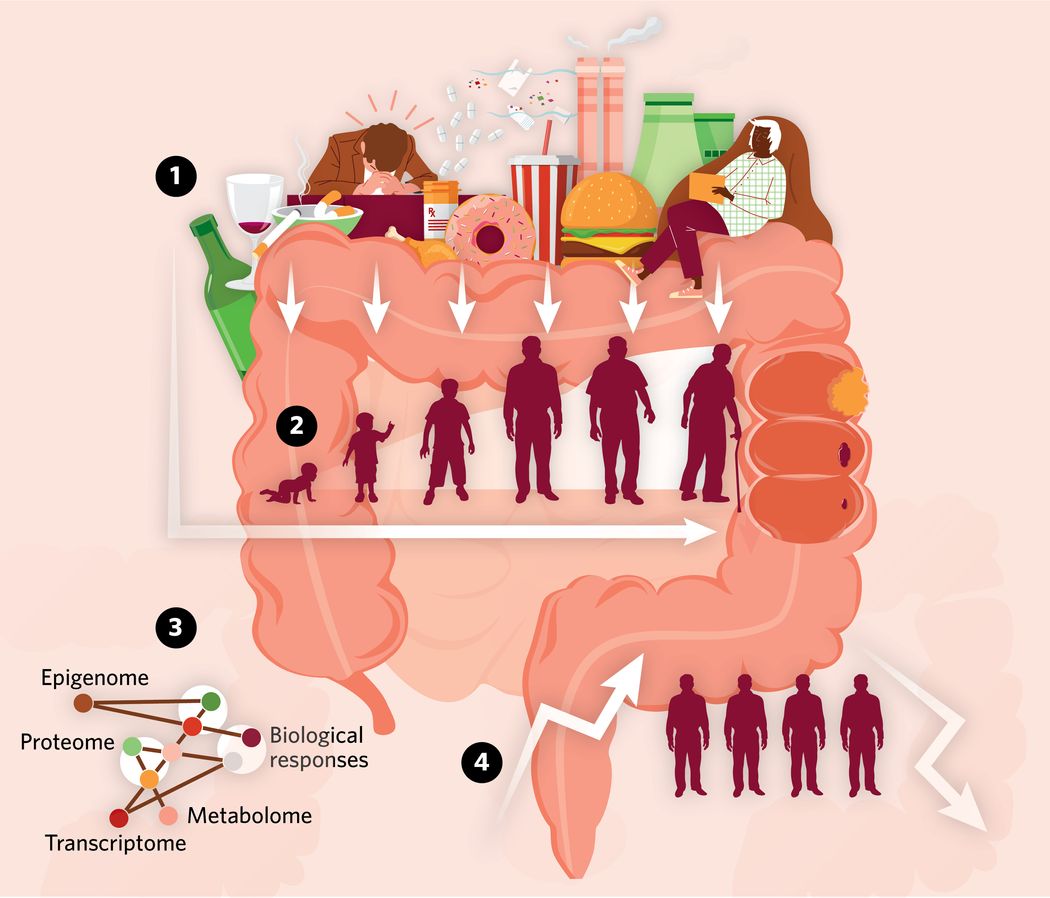

A Lifetime of Environmental Exposures May Be Fueling Early-Onset CancersSince the 1990s, colorectal cancer cases and mortality rates have dropped in those aged 50 and older, but cases have risen in younger populations. While research has focused on the genome for genetic clues, recent studies emphasize the significant role of the exposome. modified from © istock.com, Olga Naumova, azatvaleev, Jobalou, lemono, AKO, KrizzDaPaul, dondesigns, Kudryavtsev Pavel, WEERASAK PITHAKSONG; designed by erin lemieux 1) The exposome refers to the totality of the environmental factors a person is exposed to throughout their life. From processed foods to synthetic chemicals, a growing list of non-genetic factors may be driving the rising rates of chronic diseases and cancers. 2) Generational shifts in the types, timing, and duration of environmental exposures may be contributing to the alarming increase in early-onset cancers observed in younger populations. 3) Scientists are using a multiomics approach to examine the effects of nongenetic factors on cells and molecules. 4) They hope these insights will lead to new prevention strategies and precision medicine approaches, aiding the most affected generations and reversing the trend for future ones. |

The last few decades have also experienced a radical shift in other consumption patterns, production processes, and lifestyle choices compared to those of previous generations. Factors like in utero exposures to chemicals, chronic sleep disruptions, antibiotics, a disrupted microbiome, stress levels, pollution, and pervasive environmental contaminants like pesticides and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), or so-called “forever chemicals” have entered the arena as potential drivers of early-onset cancer. Although many of these risk factors seem compelling, the data are limited, and rigorous experiments and large-scale studies are still needed to make any definitive conclusions.

A Grand Exploration of the Exposome

Recognizing this gap in understanding, Cancer Grand Challenges, a global research initiative founded by Cancer Research UK and the National Cancer Institute, listed early-onset cancers as one of the toughest and most pressing challenges in cancer research. In 2023, they put out a call for ambitious and bold research proposals that aim to drive significant advancements in the understanding, prevention, and treatment of early-onset cancer. Chan, along with Yin Cao, a molecular cancer epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis, submitted a set of projects that are designed to explore more deeply the established risk factors and understand how they may operate in different phases of the life course, but also to hopefully discover new risk factors.

To tackle the grand challenge, Chan and Cao assembled a global team of experts in gut microbiome, immunology, epidemiology, genetics, bioinformatics, and patient advocacy research areas. “We formed the team with the understanding that we needed to think about this question from a multidisciplinary perspective that also was able to think disruptively about the paradigm in which we think about risk factors for cancer and how they operate,” said Chan.

Andrew Chan, a gastroenterologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, is a co-lead on a project funded by Cancer Grand Challenges that aims to leverage data from prospective studies to identify known and novel risk factors driving early-onset colorectal cancer.

Massachusetts General Hospital

Chan and his team plan to start their investigations with a prospective study that follows millions of young individuals over time, using bioanalytical techniques to track changes in their exposomes, microbiomes, and epigenomes. They hope that their comprehensive approach will help identify risk factors that contribute to an individual’s chances of developing early-onset CRC. Then, they plan to systematically study these factors in organoids and animal models to characterize the biological effects of each risk factor across their lifespan.

“We ultimately hope to use that molecular understanding to develop novel strategies for prevention and to actually begin to test some of these interventions in human studies so that we can identify not only what's a causal risk factor, but also to clearly delineate what are potential agents that could be used in the clinic to actually reverse the alarming trends,” said Chan.

Generational Divides at the Molecular Level

Although scientists are actively exploring how non-genetic factors play a causative role in cancer risk, inherited genetic mutations remain in the spotlight. Cancer developing at a younger age than expected is a hallmark of inherited genetic mutations that increase an individual's cancer risk. For example, the most commonly known cause of hereditary CRC is Lynch syndrome, caused by germline mutations in certain mismatch repair genes that help repair damaged DNA. With a Lynch syndrome diagnosis, individuals and their families can undergo genetic counseling and take proactive steps for early cancer detection and prevention through genetic testing and regular screenings.

However, hereditary CRC alone does not explain the continued rise in early-onset cases in younger populations: Up to 20 percent of early-onset CRC cases are attributed to germline gene mutations, with around 10 percent of patients having Lynch syndrome.14,15

“The majority of these cases are sporadic, or don't have a known hereditary component, which makes the burgeoning trend of early-onset colorectal cancer more alarming,” said Andreana Holowatyj, a translational scientist at Vanderbilt University. “These findings tell us that germline genetic predisposition is not driving colorectal tumor development in the majority of young patients we are seeing get diagnosed with colorectal cancer.”

In her lab at Vanderbilt University, Andreana Holowatyj explores the genetics and biology of early-onset cancers.

Donn Jones

In a multiomics study comparing tumor and blood samples from younger and older patients diagnosed with sporadic CRC, Holowatyj found that deregulated redox homeostasis, or oxidative stress, was a distinct molecular phenotype of the early-onset samples.16 “Obesity induces alterations in redox homeostasis, which can lead to oxidative stress and other metabolic effects,” Holowatyj noted, adding that the steep rise in obesity rates since the 1970s could be one contributor to this potential distinct colorectal tumor biology of young patients.17

Knowledge regarding the molecular features of sporadic early-onset colorectal cancer is limited, with few studies evaluating the genomic differences both within this patient population and between younger and older CRC patients. Using targeted next-generation sequencing of patient tumors, Eng and her colleagues found similar overall rates of genomic alterations in tumors from younger and older patients.18 However, they did observe notable differences in genes that have prognostic implications. For example, alterations in the gene encoding the cell adhesion protein catenin beta-1 were more common in tumor samples from patients under the age of 40. Other genes, such as Kirsten rat sarcoma virus, which regulates cell proliferation, and the tumor suppressor gene adenomatous polyposis coli were more commonly altered in patients over 50. The findings also highlight distinct genetic pathways that may be influenced by age-related exposures.

To study genomic differences in early-onset CRC, Holowatyj used data collected through the American Association for Cancer Research’s Project GENIE, short for Genomics Evidence Neoplasia Information Exchange. GENIE is an international consortium that collects clinical-grade, next-generation cancer genome sequencing data from patients treated at participating institutions, including Vanderbilt University. “Project GENIE is a unique, collaborative resource that delivers a first-of-its-kind opportunity to study critical tumor biological questions, particularly across unique populations, whereas this would be otherwise challenging in a single institution capacity,” said Holowatyj.

Holowatyj and her colleagues previously found that patients who identified as Black had worse survival outcomes following an early-onset CRC diagnosis compared to White patients.19 In addition, young males with CRC had poorer survival versus females. “This really piqued my interest in what could potentially be driving this disproportionate disease burden for our young patients,” said Holowatyj. Her team utilized GENIE data to investigate tumor mutational burden as well as individual somatic cancer gene mutation patterns specific to young patients diagnosed with CRC, analyzing the data by self-identified race/ethnicity as well as by sex.

Among patients with non-hypermutated tumors—which Holowatyj and her team used as proxy for sporadic cases, as hypermutated tumors suggest the disease could be hereditary—they found that patients who identified as Black had a significantly higher tumor mutational burden compared to those who identified as non-Hispanic White.20 In contrast, no differences were observed between individuals identifying as Asian and non-Hispanic White. These patterns were consistent among patients with patients with late-onset, non-hypermutated CRC.

“One of the most intriguing findings was the discovery of multiple genes that we saw differ in mutation patterns by patient sex,” said Holowatyj. “This points to [how much] more there is to discover with the complex interplay of biological sex and effects of genetics, hormones and the environment. How these may drive differences in sex-specific outcomes, particularly for young patients, is an important area that my team is currently investigating.”

“Despite the number of cases we were able to accumulate, this is still the tip of the iceberg as to our knowledge in early-onset colorectal cancer biology and disparities,” said Holowatyj. Using resources like GENIE, as well as international collaborations, she hopes to illuminate the mechanisms driving carcinogenesis in young patients and determine how these may vary across population groups in a meaningful way that could inform personalized prevention, diagnostic, and treatment strategies.

However, she emphasized that biology and genetics is only one factor playing a role in cancer development. “When I think of disparities [in cancer], I think about them as a constellation,” said Holowatyj. The molecular observations are one point amidst a group of factors that includes community health, such as access to health care, other systemic factors, and person-level features, including an individual’s exposome.21 “Our evidence points to the need for a comprehensive, cells-to-society approach to be able to elucidate key drivers and develop both therapeutic and community-based interventions that together will reduce the growing burden of early-onset cancers and improve clinical outcomes,” she added.

Screen Time vs. Screening Time: A Health Wake-Up Call for the Digital Generations

Understanding the causes of early-onset CRC is crucial for developing targeted treatments for the generations most at risk. Uncovering these factors could improve current care but also take steps to reverse this alarming trend for future generations.

Despite recent advances in medical research, the causes of early-onset CRC remain poorly understood and the field is still in the early stages of uncovering the complexities of this disease. Large-scale genomics studies will be vital for pinpointing genetic alterations, but additional tools are needed for more mechanistic studies into the downstream consequences of genomics alterations. To this end, researchers like Chan and Holowatyj hope to use patient-derived organoids and human cell lines to uncover the molecular mechanisms driving early-onset CRC and identify potential therapeutic targets.

If we can diagnose patients earlier, before they're diagnosed with stage 4 disease, we can still cure them.

— Cathy Eng, Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Although the wheels are in motion, these studies will take time. In the meantime, researchers and clinicians studying early-onset CRC are working to raise awareness among Generation Xers and Millennials and also physicians. “With colorectal cancer, one of the interesting things that we've seen from our clinical study, there still remains a lot of healthcare, professional education,” said Holowatyj. She mentioned that many patients visiting her clinic who present with stage 4 disease previously had their symptoms—changes in bowel habits, blood in their stool, or pain—dismissed or misdiagnosed as a hemorrhoid or irritable bowel syndrome because of their age. “Because they looked so healthy and because they don't have any family history, people presume that that's not possible,” added Eng.

A key part of their educational efforts is updating the public on the latest changes to screening guidelines. In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) lowered the recommended screening age from 50 to 45. Eng emphasized the importance of early diagnosis, stating, “If we can diagnose patients earlier, before they're diagnosed with stage 4 disease, we can still cure them.” Their message seems to be getting through. A recent study found an uptick in uptake of preventative CRC screenings for individuals aged 45 to 49 in the 20 months following the USPSTF’s new recommendations.22

Early-onset cases of CRC are part of a broader trend; other cancers, including breast and pancreatic cancers, are also rising in younger populations.23-25 Understanding the factors behind early-onset CRC could provide valuable insights into this worrying trend and help improve prevention, detection, and treatment across various cancer types. “We view [early-onset CRC] as being kind of a sort of exemplar for potentially thinking about this type of research in other early-onset cancers,” said Chan.

Disclaimer: All interviews for this story were conducted in 2024, prior to any new administration policy changes.

- Siegel RL, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8):djw322.

- Zhao J, et al. Global trends in incidence, death, burden and risk factors of early-onset cancer from 1990 to 2019. BMJ Oncology. 2023;2(1):e000049.

- Arnold M, et al. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut. 2017;66(4):683-691.

- American Cancer Society. Colorectal cancer facts & figures 2023-2025. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2023.

- Siegel RL, et al. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(3):233-254.

- Laconi E, et al. Cancer as a disease of old age: Changing mutational and microenvironmental landscapes. Br J Cancer. 2020;122(7):943-952.

- Hofseth LJ, et al. Early-onset colorectal cancer: Initial clues and current views. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(6):352-364.

- Li H, et al. Association of body mass index with risk of early-onset colorectal cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(11):2173-2183.

- Archambault AN, et al. Nongenetic determinants of risk for early-onset colorectal cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021;5(3):pkab029.

- Kim NH, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic young adults (20-39 years old). Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(1):115-122.

- Viennois E, et al. Dietary emulsifier-induced low-grade inflammation promotes colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2017;77(1):27-40.

- Wang L, et al. Association of ultra-processed food consumption with colorectal cancer risk among men and women: Results from three prospective US cohort studies. BMJ. 2022;378:e068921.

- Juul F, et al. Ultra-processed food consumption among US adults from 2001 to 2018. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022;115(1):211-221.

- Seagle HM, et al. Clinical multigene panel testing identifies racial and ethnic differences in germline pathogenic variants among patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(26):4279-4289.

- Pearlman R, et al. Prevalence and spectrum of germline cancer susceptibility gene mutations among patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):464-471.

- Holowatyj AN, et al. Distinct molecular phenotype of sporadic colorectal cancers among young patients based on multiomics analysis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(4):1155-1158.e2.

- Ulrich CM, et al. Energy balance and gastrointestinal cancer: risk, interventions, outcomes and mechanisms. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(11):683-698.

- Lieu CH, et al. Comprehensive genomic landscapes in early and later onset colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(19):5852-5858.

- Holowatyj AN, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in survival among patients with young-onset colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(18):2148-2156.

- Holowatyj AN, et al. Racial/ethnic and sex differences in somatic cancer gene mutations among patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 2023;13(3):570-579.

- Holowatyj AN, et al. Gut instinct: A call to study the biology of early-onset colorectal cancer disparities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21(6):339-340.

- Siddique S, et al. USPSTF colorectal cancer screening recommendation and uptake for individuals aged 45 to 49 years. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(10):e2436358.

- Sung H, et al. Differences in cancer rates among adults born between 1920 and 1990 in the USA: an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9(8):e583-e593.

- Koh B, et al. Patterns in cancer incidence among people younger than 50 years in the US, 2010 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(8):e2328171.

- The Lancet Gastroenterology Hepatology. Cause for concern: The rising incidence of early-onset pancreatic cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(4):287.