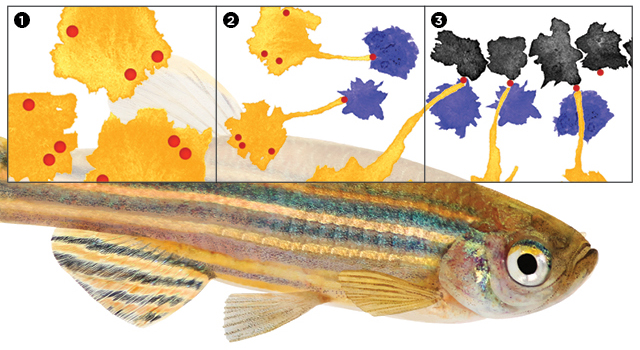

CELL ESCORT: As they mature, zebrafish develop a pattern of black stripes made up of dark pigmented cells called melanophores. Researchers have now shown that organization of the pattern is achieved by the ferrying activity of immune cells called macrophages. First, xanthoblasts (orange)—precursors to yellow pigment cells residing in zebrafish skin—form vesicles (red) filled with signaling molecules at their surface (1). Then, macrophages (blue) pick up these vesicles, which remain attached to xanthoblasts by thin filaments (2). On encountering a melanophore (black), the macrophage deposits its cargo on the surface of the pigment cell (3). This long-distance communication represents an entirely new function for macrophages. ZEBRAFISH © ISTOCK.COM/MIRKO_ROSENAU

CELL ESCORT: As they mature, zebrafish develop a pattern of black stripes made up of dark pigmented cells called melanophores. Researchers have now shown that organization of the pattern is achieved by the ferrying activity of immune cells called macrophages. First, xanthoblasts (orange)—precursors to yellow pigment cells residing in zebrafish skin—form vesicles (red) filled with signaling molecules at their surface (1). Then, macrophages (blue) pick up these vesicles, which remain attached to xanthoblasts by thin filaments (2). On encountering a melanophore (black), the macrophage deposits its cargo on the surface of the pigment cell (3). This long-distance communication represents an entirely new function for macrophages. ZEBRAFISH © ISTOCK.COM/MIRKO_ROSENAU

The paper

D.S. Eom, D.M. Parichy, “A macrophage relay for long-distance signaling during postembryonic tissue remodeling,” Science, doi:10.1126/science.aal2745, 2017.

Macrophages are increasingly appreciated as important mediators of many physiological processes, from homeostasis to tissue remodeling. But the recent discovery of a new role for the immune cells comes from an unexpected source: the stripes that give zebrafish their name.

Widely used as a model organism for developmental biology because the young are transparent, Danio rerio as adults have a characteristic black-and-yellow striping that runs the lengths of their bodies. “Nobody really pays much attention to the later stages” of the fish’s development, says University of Virginia biologist David Parichy. “But for years, [our lab] has worked on pigmentation and pattern formation.”

Zebrafish pigmentation is directed ...