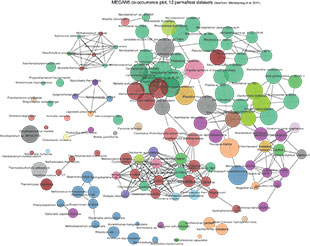

PROBING THE METAGENOME: The MEGAN5 program allows for taxonomic, functional, and comparative analyses. Here it displays taxonomic results from 12 samples of permafrost as a co-occurrence plot, which allows visualization of the species represented in the samples. Lines between the circles indicate the species that have a high probability of occurring together in a sample.

PROBING THE METAGENOME: The MEGAN5 program allows for taxonomic, functional, and comparative analyses. Here it displays taxonomic results from 12 samples of permafrost as a co-occurrence plot, which allows visualization of the species represented in the samples. Lines between the circles indicate the species that have a high probability of occurring together in a sample.

See full size: JPG | PDF DANIEL HUSONWith sequencing reads getting longer and cheaper in the past few years, researchers have begun ambitious efforts to catalog the genomic richness and variation within complex microbial and viral communities. So-called metagenomics studies involve collecting a sample of cells from their environment, breaking them open, chopping their DNA into pieces, and running the fragments on a sequencing machine.

Metagenomic analyses are more computationally demanding than genomic analyses because you’re working with a mix of diverse genomes rather than DNA from a more homogeneous microbial population. And even more than for genomics, one of the biggest challenges for metagenomics is making sense of the resulting data, says evolutionary biologist Jonathan Eisen of the University of California, Davis. Not only do scientists want to understand what microorganisms are present in a particular environment—not easy, considering that an average of 99 percent of them have never been cultured —and at what levels, but also what their functions are and how they compare with one another. “Sequencing is cheap, but that doesn’t mean you can put a community into a sequencer and make sense of it,” Eisen ...