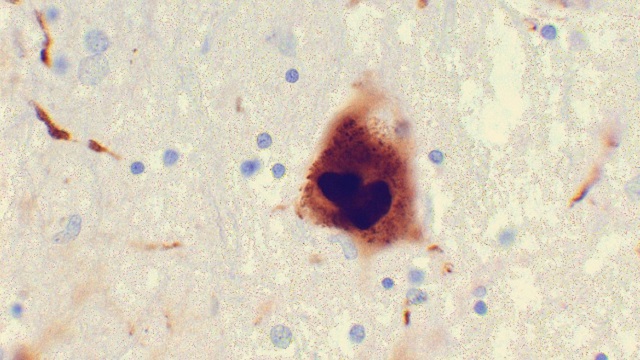

Photomicrograph of a region of substantia nigra in a Parkinson’s patient showing Lewy bodiesWIKIMEDIA, SURAJ RAJANA growing body of evidence points to an intimate relationship between the gut and the brain—both in health and disease. In presentations at the Society for Neuroscience meeting this week in Washington, D.C., researchers discussed recent findings that support a link between gastrointestinal tract health—and the microbiome, in particular—and neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

Photomicrograph of a region of substantia nigra in a Parkinson’s patient showing Lewy bodiesWIKIMEDIA, SURAJ RAJANA growing body of evidence points to an intimate relationship between the gut and the brain—both in health and disease. In presentations at the Society for Neuroscience meeting this week in Washington, D.C., researchers discussed recent findings that support a link between gastrointestinal tract health—and the microbiome, in particular—and neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

Comparing the gut microbes of mice with Alzheimer’s-like pathology and healthy controls, Harpreet Kaur of the University of North Dakota and colleagues found noticeable differences in microbiome composition. Treating the diseased mice with probiotics decreased gut leakiness and inflammation, which had been elevated in these animals, and boosted memory performance.

In a separate study, Ishita Parikh of the University of Kentucky and colleagues took a similar approach, but instead of comparing the microbiomes of diseased and healthy animals, they compared mice with different variants of the APOE gene, which is strongly linked to Alzheimer’s risk in people. Once again, the researchers found distinct differences in the microbial profiles of the mouse strains, suggesting that “gut microbiome is associated with APOE genotype,” at least in this ...