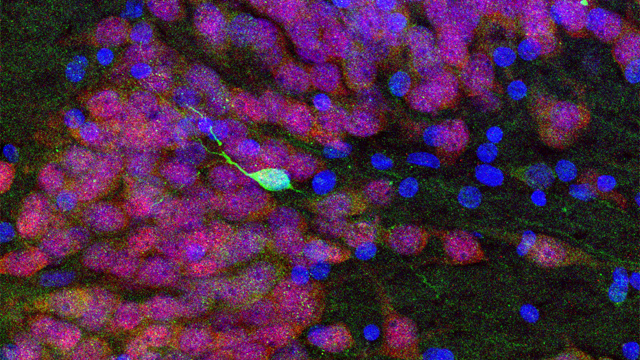

Stained tissue from a 13-year-old human hippocampus shows a single young neuron (green), surrounded by mature neurons (red) and cell nuclei (blue).COURTESY OF SHAWN SORRELLSNew neurons may not develop in the adult human brain as neuroscientists for years have come to believe. Researchers studying postmortem brain tissue of humans found evidence of neural precursor cells and immature neurons in fetuses, infants, and teenagers, but not in adults over 18 years of age. The findings, published today (March 7) in Nature, contradict two decades of research showing that human adult hippocampi—epicenters of learning and memory in the brain—generate new neurons and raise questions about how scientists study neurogenesis.

Stained tissue from a 13-year-old human hippocampus shows a single young neuron (green), surrounded by mature neurons (red) and cell nuclei (blue).COURTESY OF SHAWN SORRELLSNew neurons may not develop in the adult human brain as neuroscientists for years have come to believe. Researchers studying postmortem brain tissue of humans found evidence of neural precursor cells and immature neurons in fetuses, infants, and teenagers, but not in adults over 18 years of age. The findings, published today (March 7) in Nature, contradict two decades of research showing that human adult hippocampi—epicenters of learning and memory in the brain—generate new neurons and raise questions about how scientists study neurogenesis.

“The results highlight our need for new and better tools to study adult neurogenesis to ensure we are using the right markers,” Fred “Rusty” Gage, a neuroscientist at the Salk Institute who generated foundational evidence of adult human neurogenesis in 1998, tells The Scientist. The paper, he notes, reveals gaps in researchers’ understanding of neurogenesis, which additional studies will fill in.

Much of the work on neurogenesis has been done in animals. In the latest study, Shawn Sorrells and Mercedes Paredes of the University of California, San Francisco, and their colleagues wanted to search for evidence of neurogenesis in human brains and test a different technique compared with what had been used in the past. The team collected postmortem and postoperation hippocampal tissue from 59 ...