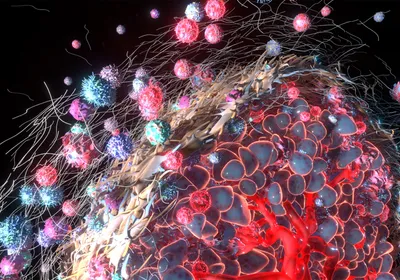

An artificial ovary, shown, helped mice ovulate and give birth to healthy pups.IMAGE COURTESY OF NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITYAbout 10 percent of cancer survivors are women under 40. Once they undergo chemotherapy or radiation, they may no longer be able to have a baby. So scientists are working to create artificial ovaries that could give these cancer survivors a new option for conceiving a child.

An artificial ovary, shown, helped mice ovulate and give birth to healthy pups.IMAGE COURTESY OF NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITYAbout 10 percent of cancer survivors are women under 40. Once they undergo chemotherapy or radiation, they may no longer be able to have a baby. So scientists are working to create artificial ovaries that could give these cancer survivors a new option for conceiving a child.

The artificial ovary is a “house” for egg-producing follicles, just like the original ovary, Christiani Amorim, who studies animal reproduction at Université catholique de Louvain in Belgium, tells The Scientist by email. “We aim to recreate the right conditions the follicles need to survive.”

Several groups are competing and collaborating to develop the perfect artificial ovary, and so far studies show it is possible to use the synthetic organ to restore ovarian function in mice. Perfecting the structure, stiffness, and capabilities of the human artificial ovary is now the focus, with teams nearing the point where they could start testing them out in women. If shown to work, this structure could have other uses too, in everything from toxicology studies to postponing childbearing to possibly ...