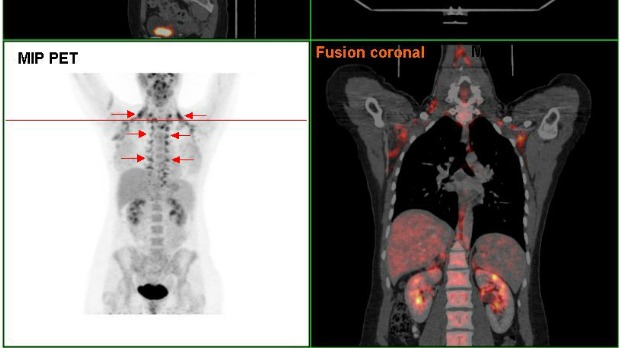

Arrows indicate where most brown fat is found in the human body.WIKIPEDIA, HGG6996

Arrows indicate where most brown fat is found in the human body.WIKIPEDIA, HGG6996

Brown fat—the form of adipose tissue that burns, rather than stores, energy—was only recently discovered to exist in adult humans. For decades, researchers knew it was present in rodents, whose brown fat reserves are quite large. But it wasn’t until the advent of PET-CT scans that allowed scientists to finally image brown fat in people, about six years ago.

"If we are honest, we still don’t know what the function is of the brown fat, especially in humans,” says Patrick Schrauwen, who, along with his colleagues at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, was one of the first researchers to identify brown fat in adult humans. But scientists do know what the tissue is capable of: chewing up calories. This property has made brown fat a ...