Long before it had a name, signs of Parkinson’s disease appeared in ancient medical texts. These historical accounts described individuals who experienced tremors and difficulty moving, although it wasn’t until 1817 that English surgeon James Parkinson gave the condition its first clinical identity. He described it as the “shaking palsy,” from a case series about six individuals. At the time, doctors considered it to be a rare disorder.

Two centuries later, Parkinson’s disease is no longer a medical rarity. It is typically diagnosed in individuals over the age of 60, but it can develop in people as early as their 20s. Its incidence has more than doubled over the past 20 years and is expected to double again in the next 20, affecting an estimated 25 million individuals globally.1 According to the Global Burden of Disease study, it is now one of the fastest-growing neurological disorders in the world, outpacing stroke and multiple sclerosis.2 The disease causes the progressive death of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra of the brain, which is responsible for modulating motor movement and reward functions. As dopamine levels deteriorate, the neurodegeneration robs people of movement—scientists believe this process starts about a decade or two before these motor symptoms emerge.

“It’s not just a movement disorder,” explained Sule Tinaz, a movement disorders neurologist and neuroimaging researcher at Yale University. The cardinal features of tremors, rigidity, and slowed movement, or bradykinesia, are only the tip of the iceberg. She added, “[Parkinson’s disease] affects cognition, it affects mood, and it affects sleep. It’s the whole package, and it’s quite complex.” Being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease can be deeply overwhelming and disheartening. There is currently no cure, and as a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, its symptoms can only be managed—and typically worsen over time.

Currently, people with Parkinson’s disease primarily rely on pharmacological treatments, which either replace dopamine or mimic its effects to treat motor symptoms. In some cases, neurosurgical options like deep brain stimulation can help manage their symptoms.

As a neurologist, I can see every day in clinical practice that my patients who do best are the ones who faithfully exercise.

—Bastiaan Bloem, Radboud University Medical Center

More recently, clinical trials have explored the potential of repurposing GLP-1 receptor agonists—such as exenatide—for Parkinson’s disease.3,4 These drugs, originally developed for type 2 diabetes, have also shown promise as possible Parkinson’s disease-modifying treatments in nonclinical cell cultures. Although initial clinical trials for exenatide did not slow disease progression in a Phase 3 study, researchers and clinicians continue to explore other possible drugs for Parkinson’s disease.5 However, because medication typically only targets one of the many elements of the complex and multifaceted pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease, others look to nonpharmacological treatments to outpace its progression.

“What can we do to delay the disease course or even reverse it or halt it? That piece is missing,” said Tinaz. Because of this, many researchers and clinicians have turned to prescribing exercise. Over the last two decades, exercise has emerged as one of the most promising nonpharmacological treatments available—not just for managing symptoms alongside drugs, but for potentially altering the trajectory of Parkinson’s disease itself.

Fighting Neurodegeneration One Workout at a Time

Exercise plays a vital role in maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Research consistently shows that regular physical activity—especially aerobic exercise—is far more beneficial than living a sedentary, inactive life. This includes a wide variety of activities such as running, dancing, cycling, martial arts, boxing, and more.

For Bastiaan Bloem, a neurologist at the Radboud University Medical Center and cofounder of ParkinsonNet, a healthcare network of professionals and people living with Parkinson’s disease, the value of exercise is both personal and professional. “Exercise was my bread and butter,” said Bloem, whose father was his sports teacher in high school. Bloem later played as a semi-professional volleyball player. “As a neurologist, I can see every day in clinical practice that my patients who do best are the ones who faithfully exercise,” he said. On the flip side as a scientist, Bloem also emphasized the need for solid evidence to demonstrate that exercise deserves to be included as a reimbursed part of standard medical care for patients.

Bastiaan Bloem, a neurologist at the Radboud University Medical Center, studies how various forms of exercise can benefit patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Bastiaan Bloem

The benefits of exercise extend beyond the physical, such as improved mobility and balance, to include significant mental advantages. It can elevate mood by releasing feel-good endorphins, enhance sleep quality, and, over time, reduce the risk of chronic diseases.6

Not only that, but animal and human studies have demonstrated that exercise protects the brain.7-10 It stimulates the production of growth factors that help create new nerve connections, leading to improved cognitive function. These features suggest that individuals with Parkinson’s disease might benefit from improving their overall health, which could lead to disease-modifying effects.

However, it’s easier said than done. Many know of the benefits of exercise, yet few people do it. This is sometimes the case with patients with Parkinson’s disease as increasing physical disability and a lack of confidence make them more likely to remain inactive. How could Bloem and others motivate their patients to exercise, stay motivated, and retain this lifestyle change?

In 2007, he and his colleagues launched their ParkFit study in the Netherlands, which provided participants with a dedicated lifestyle coach to motivate them and tailor individual programs to their needs.11 Participants recorded their activities over the course of two years. “Rather than telling people to go to the gym, we told them to use their bike instead of their car to do shopping and to take the stairs instead of the elevator,” said Bloem. While overall activity increased, their primary outcome was the net sum of indoor and outdoor activities. Although outdoor activity increased at the expense of the former, the net result was a zero-sum game.

However, Bloem noted that their other outcomes, such as quality of life, ambulatory activity through a wearable sensor, and fitness (through a six-minute walk test) were positive and warranted further investigation.12

Undeterred, Bloem’s team altered their approach to improve adherence to these programs through gamifying exercise, or “exergaming.” This study, called Park-in-Shape, placed stationary bikes in the participants’ homes and asked them to do an aerobic workout at 80 percent of maximum cardiac output for 30 minutes three times per week, and the control group did stretching exercises for 30 minutes three times per week.13 Instead of an in-person coach, the team developed a custom app with a variety of games to motivate people during their workout.

“[In one game], we converted the PacMac game for use on the bicycle so that the faster you biked, the more monsters you killed,” said Bloem. After their workout, the same app rewarded both sets of participants for their efforts. At the end of six months, the researchers saw that the control group declined over time, which was expected in a progressive disease such as Parkinson’s disease. The intervention group, however, remained stable, and the exercise improved motor movement.

When the researchers performed brain imaging, Bloem remarked that there was a bit of atrophy happening over six months’ time in the control group, but not in the exercise group.13 Instead, they found that the brain started to make new functional connections between the damaged basal ganglia—the affected area in Parkinson’s disease—and the healthy brain cortex. “[This finding] offered us a mechanistic explanation for the clinical effects that we had published,” said Bloem.

Similar results emerged from the SPARX trial (Study in Parkinson Disease of Exercise), which examined the effects of exercise intensity on people with de novo Parkinson’s disease—those recently diagnosed but who had not yet begun medication. The trial compared moderate-intensity (60–65 percent of maximum heart rate) and high-intensity (80–85 percent) treadmill workouts. Those who exercised at high intensity showed significantly less disease progression, suggesting that vigorous aerobic activity may have a protective effect in early-stage Parkinson’s disease.14 Building on this work, a larger Phase 3 clinical trial, SPARX3, is currently underway. This expanded study includes physical and cognitive assessments, along with brain imaging, to determine which level of intensity yields the greatest benefit.

Combating Parkinson’s Disease Symptoms Through Karate

Much like how some people are more motivated to work out with a gym buddy, several studies have partnered with community-based programs. These efforts not only support physical health but also foster social connection, camaraderie, and accountability.

Jori Fleisher, a movement disorders neurologist at Rush University, focuses on designing better models of care and care partner support for Parkinson’s disease and related disorders.

Rush University Medical Center

Jori Fleisher, a movement disorders neurologist at Rush University, recalled how one of her patients came to her with an idea. He was already doing everything one would expect for an active lifestyle—strength training, aerobic exercises, physical therapy, yoga, and tai chi. In short, he ticked all the boxes. But he had one question: If boxing is gaining popularity for Parkinson’s Disease through programs like Rock Steady Boxing, which was founded in 2006 by Scott Newman to help manage his own tremors, why hadn’t anyone explored karate?15,16

Rock Steady Boxing, a non-contact program, has spread across the United States and to 14 other countries. It involves punching heavy bags, footwork drills, stretching, resistance exercises, and aerobic training. The patient’s curiosity about karate stuck with Fleisher, who pointed out that karate shares many of the same benefits as boxing. “[Karate] combines a lot of the same aerobic activity and large amplitude movement, which we know from physical therapy is really beneficial for people with Parkinson’s,” she said. But Fleisher also saw something else in karate: the cognitive benefits. Karate involves learning patterns of movement and working memory, areas of cognition that are often impaired in people with Parkinson’s disease.

Inspired by this, Fleisher designed a study with her patient and John Fonseca, a karate world champion who runs karate schools in Chicago. Together, they created a new program called Kick Out PD, a karate-based program designed specifically for people with mild to moderate Parkinson’s disease. They held community-based classes twice per week for 10 weeks, with participants evaluated for changes in their quality of life. Many reported feeling moderately to significantly better after the program.17

Encouraged by these results, Fleisher and her colleagues aimed to up the ante—to see the differences between two groups of people.18,19 One group participated in twice-weekly karate classes for six months, while the other group continued with their usual exercise routines. At the six-month mark, researchers tested both groups and then had the second group begin karate training as well. Was there a difference if an individual did karate for a year over those who only did six months?

However, the 12-month follow-up visits for the study were scheduled for March 2020 just as the US went into lockdown due to COVID-19. Fleisher was concerned about how she and her team could support their participants in the midst of a shutdown.

Thankfully, Fonseca quickly adapted. He recorded karate sessions from the dojo and uploaded them online so participants could continue practicing at home. “The camaraderie was tremendous,” Fleisher said. Overall, the participants who kept up with their karate exercises experienced an improved quality of life and adhered to the regimen. Once it became safe to gather outdoors with proper social distancing, they resumed in-person classes in parks and open spaces. “They were just doing it on their own,” she remarked. “Some participants who started Kick Out PD in 2018 or 2019 are still actively involved today. They have even progressed through belt testing just like any other student in a traditional karate program.”

Fleisher often hears updates from her patients during clinic visits. “They’ll talk about each other and brag, saying things like, ‘You should see so-and-so do a spin kick!’” she said. For her, these anecdotes are more than heartwarming. Fleisher described these accounts as “unbelievably powerful visuals” of what people with Parkinson’s disease can achieve when given the right tools and community. Global efforts have also been underway to further investigate the benefits of karate training with clinical studies comparing its effects to activities like dance—particularly in improving balance, coordination, and mood.20,21

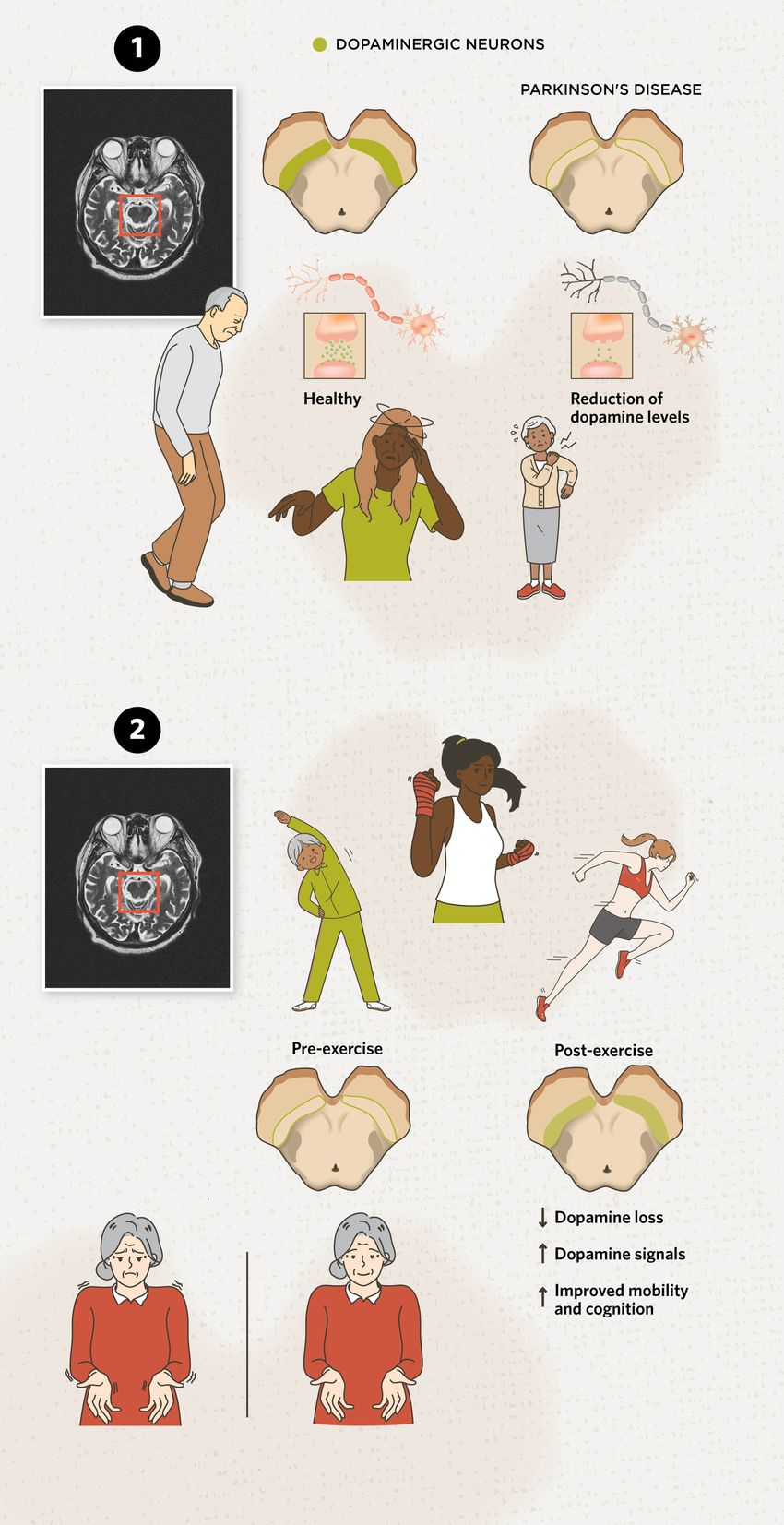

Neuroprotective Effects of Exercise in Parkinson’s DiseaseExercise alleviates Parkinson’s disease symptoms and may protect the brain from degeneration, offering a complementary approach to traditional treatments. Parkinson’s disease is a degenerative disease with a relentless trajectory of neurological destruction that results in motor and non-motor symptoms. Researchers and clinicians are increasingly hopeful that exercise, along with pharmaceutical approaches, can help slow its debilitating effects, improve mobility, and offer neuroprotective benefits.  modified from © istock.com, mr.suphachai praserdumrongchai, Sakurra, solar22, Mikhail Seleznev, yuki goto, Syuzanna Guseynova, linden, Aleksei Morozov; designed by erin lemieux 1) Dopamine Deficiency in Parkinson’s Disease: Parkinson’s disease is generally characterized by the degradation of dopamine-producing neurons in the brain, especially in the substantia nigra region. Dopamine is a crucial neurotransmitter for various brain functions, including motivation, cognitive functions, movement. Because of this loss, it can result in motor symptoms such as tremors, bradykinesia (slowed movement), rigidity, and difficulty maintaining balance. 2) Brain Gains from Exercise: Because Parkinson’s disease lacks a cure, treatments can only alleviate symptoms. Aerobic exercise is linked to improved mood, mobility (such as coordination), and cognitive ability compared to more sedentary people with Parkinson’s disease.7,14,18,19 But what changes occur in the brain? Exercise helps prevent brain atrophy, supports the formation of new connections, and slows the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in Parkinson’s disease.13 Additionally, one study found that neuromelanin—a dark pigment found in dopamine-producing neurons—in the substantia nigra, and dopamine transporter levels increased after exercise, indicating improved brain function.22 While researchers continue to study which types, intensities, and volumes of exercises are most effective for alleviating Parkinson’s disease symptoms, there is widespread agreement that any form of physical activity is beneficial. Plus, it should be tailored to each person’s preferences to support long-term adherence and outcomes. |

While various forms of exercise have been linked to positive changes in Parkinson’s disease symptoms, researchers wanted to investigate whether there were measurable changes in the brain at the neuronal level. Tinaz and her colleagues partnered with a local exercise program called Beat Parkinson’s Today which offers online and in-person classes throughout Connecticut. Michelle Hespeler, a former physical education teacher who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease at the age of 40, developed the program, which was inspired by Bloem’s ParkFit exercise program.

In this collaboration, Tinaz and her team enrolled 10 patients with early-stage Parkinson’s disease to undergo six months of high-intensity aerobic exercise (strength, cardio, power exercises, and boxing) three times per week.22 The researchers performed pre- and post-exercise clinical assessments and brain imaging, using two different imaging modalities. One was a magnetic resonance imaging scan that measured the amount of neuromelanin—a dark pigment found in dopamine-producing neurons—in the substantia nigra. A loss of neuromelanin is a hallmark of Parkinson’s disease pathology. The second scan was a positron emission tomography scan that measured dopamine transporter (DAT) availability. DAT is a protein that helps neurons maintain proper dopamine levels, and its levels decrease in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Kick Out PD is a community-based karate program designed to help people with Parkinson’s disease.

Jori Flesher

So, a reduction of both neuromelanin and DAT levels is expected in the natural course of the disease, reflecting reduced dopamine signals. Tinaz hoped that exercise would slow or lessen this decline. Indeed, the treatment exceeded her expectations and not only slowed the neurodegeneration process, but it may have also enhanced neuronal function. “In fact, after six months of exercise, the neurons actually produced stronger dopamine signals.” She added that this may be a result of the dopamine-producing neurons becoming healthier.

[Karate] combines a lot of the same aerobic activity and large amplitude movement, which we know from physical therapy is really beneficial for people with Parkinson’s.

—Jori Fleisher, Rush University

Tinaz expressed her excitement at the pilot study’s results. “If we can validate our findings [in a large cohort], it can be a disease-modifying intervention,” she said. She also emphasized the powerful impact exercise can have on a person’s mindset. “Once people know what a difference they can make in their lives by just exercising, they become more confident. They don’t feel like passive victims facing this disease.” Tinaz recalled one particularly moving case: a woman diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in her late 70s who was initially devastated. “In her own words, she told me, ‘I was just sitting in the chair feeling hopeless and helpless. I thought there was nothing else left for me to do.’” But after becoming involved in the program, Tinaz said that all participants became more energized and confident.

Because exercise varies widely in type, intensity, and benefit, researchers are continuing to explore and validate which forms are most effective for people with Parkinson’s disease. Exercise is an umbrella term, and identifying the right “dose”—whether it’s aerobic, resistance, high- or low-intensity—is an ongoing focus. “We need more research to be able to answer these questions and to be able to come up with individualized exercise prescriptions for people,” said Tinaz.

Importantly, exercise can potentially be a protective lifestyle factor, a disease-modifying therapy, and an effective symptomatic treatment. Bloem noted that “exercise ticks all the boxes.” It’s increasingly recognized as a core part of Parkinson’s disease management, working in concert with medication and other lifestyle interventions such as sleep, stress management, and nutrition. The goal isn’t to replace traditional medication but to amplify its benefits through a synergistic approach.

While Tinaz acknowledged the progress made in this area, she also emphasized a critical gap: translating knowledge into practice. There is also the need to understand the barriers to exercise at the individual, healthcare systems, and societal levels, and to develop comprehensive strategies. She’s hopeful that ongoing efforts including evidence-based guidelines from the Parkinson’s Foundation, the American College of Sports Medicine, Bloem’s ParkinsonNet, and other resources will help bridge that gap. With greater awareness, improved access, and stronger support systems, exercise could reshape the way Parkinson’s disease is managed in the years to come.

“The most important takeaway is that it doesn’t matter which exercise you do. It matters that you do it and that you stick with it. Exercises are the best neuroprotective thing that we have and should be accessible to everyone,” said Fleisher.

- Su D, et al. Projections for prevalence of Parkinson’s disease and its driving factors in 195 countries and territories to 2050: Modelling study of Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMJ. 2025;388:e080952.

- GBD 2015 Neurological Disorders Collaborator Group. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders during 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(11):877-897.

- Li Y, et al. GLP-1 receptor stimulation preserves primary cortical and dopaminergic neurons in cellular and rodent models of stroke and Parkinsonism. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(4):1285-1290.

- Perry T, et al. Protection and reversal of excitotoxic neuronal damage by glucagon-like peptide-1 and exendin-4. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302(3):881-888.

- Vijiaratnam N, et al. Exenatide once a week versus placebo as a potential disease-modifying treatment for people with Parkinson’s disease in the UK: A phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2025;405(10479):627-636.

- Warburton DER, et al. Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. CMAJ. 2006;174(6):801-809.

- Mahalakshmi B, et al. Possible neuroprotective mechanisms of physical exercise in neurodegeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(16):5895.

- Voss MW, et al. Bridging animal and human models of exercise-induced brain plasticity. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(10):525-544.

- Mustroph ML, et al. Aerobic exercise is the critical variable in an enriched environment that increases hippocampal neurogenesis and water maze learning in male C57BL/6J mice. Neuroscience. 2012;219:62-71.

- Larson EB, et al. Exercise is associated with reduced risk for incident dementia among persons 65 years of age and older. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(2):73-81.

- van Nimwegen M, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of the ParkFit study, a randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of a multifaceted behavioral program to increase physical activity in Parkinson patients. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:70.

- van Nimwegen M, et al. Promotion of physical activity and fitness in sedentary patients with Parkinson’s disease: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f576.

- Johansson ME, et al. Aerobic exercise alters brain function and structure in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Neurol. 2022;91(2):203-216.

- Schenkman M, et al. Effect of high-intensity treadmill exercise on motor symptoms in patients with de novo Parkinson disease: A Phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(2):219-226.

- Domingos J, et al. Boxing with and without kicking techniques for people with Parkinson’s disease: An explorative pilot randomized controlled trial. J Parkinsons Dis. 2022;12(8):2585-2593.

- Chrysagis N, et al. Effect of boxing exercises on the functional ability and quality of life of individuals with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2024;14(5):1295-1310.

- Fleisher J, et al. KICK OUT PD: Feasibility and quality of life in the pilot karate intervention to change kinematic outcomes in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0237777.

- Woo K, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of karate for Parkinson’s disease yields improvements in quality of life. J Neurol Sci. 2023;455:121819.

- Fleisher J, et al. Randomized, waitlist-controlled trial of KICK OUT PD: Parkinson’s disease-specific karate yields high adherence and improved quality of life (P1-11.005). Neurol. 2023;100(17_supplement_2):2743.

- Jansen P, Dahmen-Zimmer K. Effects of cognitive, motor, and karate training on cognitive functioning and emotional well-being of elderly people. Front Psychol. 2012;3:40 .

- Dahmen-Zimmer K, Jansen P. Karate and dance training to improve balance and stabilize mood in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A feasibility study. Front Med. 2017;4:237.

- de Laat B, et al. Intense exercise increases dopamine transporter and neuromelanin concentrations in the substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2024;10(1):34.