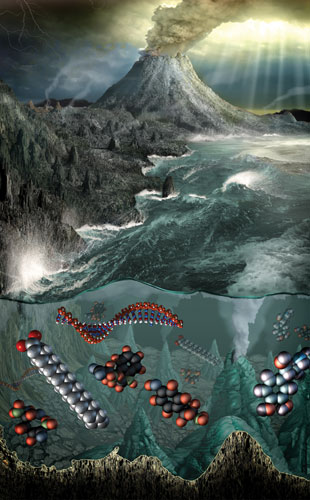

© KEVIN HANDThe ubiquity and diverse functionality of ribonucleic acid (RNA) in today’s world suggest that the information polymer could well have been the leading player early on in the establishment of life on Earth, and, in theory, it’s a logical basis for primitive life. One can readily imagine that RNA, as a catalytic molecule capable of serving as a template for its own replication, might have reproduced itself and grown exponentially in the primordial environment. Perhaps such an RNA-based proto–life-form even replicated with an appropriate level of fidelity to allow natural selection to begin directing its evolution.

© KEVIN HANDThe ubiquity and diverse functionality of ribonucleic acid (RNA) in today’s world suggest that the information polymer could well have been the leading player early on in the establishment of life on Earth, and, in theory, it’s a logical basis for primitive life. One can readily imagine that RNA, as a catalytic molecule capable of serving as a template for its own replication, might have reproduced itself and grown exponentially in the primordial environment. Perhaps such an RNA-based proto–life-form even replicated with an appropriate level of fidelity to allow natural selection to begin directing its evolution.

But there’s a snag: “The odds of suddenly having a self-replicating RNA pop out of a prebiotic soup are vanishingly low,” says evolutionary biochemist Niles Lehman of Portland State University in Oregon.

For decades, researchers from diverse fields have theorized—and argued—about how early life might have begun, and about what sparked the 3.5 billion years of evolution that led to the plethora of cell-based life that occupies almost every nook and cranny of modern Earth. Different camps emerged. So-called “metabolism first” researchers focus on understanding chemical cycles that may have materialized in a prebiotic environment and could have led to the synthesis of nucleotides and other organic molecules. Those subscribing to the theory of “genetics first” want to identify the first information molecule and understand ...