SEYCHELLES ISLANDS FOUNDATION, C ONEZIAThe Aldabra banded snail (Rhachistia aldabrae) was last sighted in 1996 and declared extinct in 2007, with the blame placed squarely on climate change. But a survey of the Aldabra atoll in the Seychelles Islands found the snail alive and well this past August, leading to questions about the original assessment of the snail’s “extinction.” Biologist Clive Hambler of the University of Oxford pointed to methodological and statistical problems with the original 2007 analysis, and called for the retraction of the paper, as he had when it was first published in Biology Letters. But the journal’s editor-in-chief Rick Battarbee said that he is not planning to pull the manuscript from the literature. “There are lots of papers that have been published in the past and subsequently were found to be inaccurate,” Battarbee told The Scientist. “The fact that someone wanted to contest these analyses, the data, or the interpretation is just standard [scientific process].”

SEYCHELLES ISLANDS FOUNDATION, C ONEZIAThe Aldabra banded snail (Rhachistia aldabrae) was last sighted in 1996 and declared extinct in 2007, with the blame placed squarely on climate change. But a survey of the Aldabra atoll in the Seychelles Islands found the snail alive and well this past August, leading to questions about the original assessment of the snail’s “extinction.” Biologist Clive Hambler of the University of Oxford pointed to methodological and statistical problems with the original 2007 analysis, and called for the retraction of the paper, as he had when it was first published in Biology Letters. But the journal’s editor-in-chief Rick Battarbee said that he is not planning to pull the manuscript from the literature. “There are lots of papers that have been published in the past and subsequently were found to be inaccurate,” Battarbee told The Scientist. “The fact that someone wanted to contest these analyses, the data, or the interpretation is just standard [scientific process].”

WIKIMEDIA, RAMAAnother paper in hot water this week is a December 2013 Nature Neuroscience paper that claimed mice could pass on odor-specific fears to their offspring. In a commentary published this week (October 15) in GENETICS, Purdue University’s Gregory Francis argues that the paper’s statistical results are “too good to be true,” calculating that the researchers’ probability of getting the pattern of successful results they did was only 0.004. “[T]he absence of unsuccessful results implies that something is amiss with data collection, data analysis, or reporting,” he wrote in his GENETICS critique. But Brian Dias and Kerry Ressler of Emory University, the authors of the Nature Neuroscience paper, stand by their results, stating that they have replicated the transgenerational effect. “Even if Francis is correct that there is a surplus of significance here . . . it doesn’t necessarily invalidate the findings,” noted Steven Goodman, a professor of medicine at Stanford University and head of a new center for improving the validity of biomedical research.

WIKIMEDIA, RAMAAnother paper in hot water this week is a December 2013 Nature Neuroscience paper that claimed mice could pass on odor-specific fears to their offspring. In a commentary published this week (October 15) in GENETICS, Purdue University’s Gregory Francis argues that the paper’s statistical results are “too good to be true,” calculating that the researchers’ probability of getting the pattern of successful results they did was only 0.004. “[T]he absence of unsuccessful results implies that something is amiss with data collection, data analysis, or reporting,” he wrote in his GENETICS critique. But Brian Dias and Kerry Ressler of Emory University, the authors of the Nature Neuroscience paper, stand by their results, stating that they have replicated the transgenerational effect. “Even if Francis is correct that there is a surplus of significance here . . . it doesn’t necessarily invalidate the findings,” noted Steven Goodman, a professor of medicine at Stanford University and head of a new center for improving the validity of biomedical research.

WIKIMEDIA, LADYOFHATSTo learn how to run on a wheel with unevenly spaced rungs, mice must be able to make new myelin, the fatty sheaths that insulate neuronal axons, according to a study published this week (October 16) in Science. Myelin is produced by non-neuronal glial cells called oligodendrocytes, suggesting that neurons are not the only important cell types when it comes to learning. “This is a very significant paradigm shift in the ways we think about how the brain changes in order to acquire information,” said the University of Michigan’s Gabriel Corfas, author of an accompanying commentary in Science and who was not involved in the research.

WIKIMEDIA, LADYOFHATSTo learn how to run on a wheel with unevenly spaced rungs, mice must be able to make new myelin, the fatty sheaths that insulate neuronal axons, according to a study published this week (October 16) in Science. Myelin is produced by non-neuronal glial cells called oligodendrocytes, suggesting that neurons are not the only important cell types when it comes to learning. “This is a very significant paradigm shift in the ways we think about how the brain changes in order to acquire information,” said the University of Michigan’s Gabriel Corfas, author of an accompanying commentary in Science and who was not involved in the research.

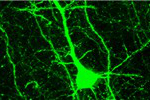

MAJA DJURISIC AND RICHIE SAPP, STANFORD The brain’s ability to alter its neuronal connections based on experience is typically halted prior to adulthood due to the the paired-immunoglobulin–like receptor B (PirB) protein; knocking out PirB led to mice having greater plasticity throughout their lives, according to a study published this week (October 15) in Science Translational Medicine. This allowed new, functional synapses to form, and even restored eye sight in animals with so-called “lazy eye.” “There is a lot of interest in the ‘critical period’ of development when the brain is plastic and undergoes a lot of changes and learning,” said Christiaan Levelt, who studies the biology of visual plasticity at the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience in Amsterdam and was not involved in this work. “This study shows that, in an adult animal, you can re-open this critical period window and get enhanced plasticity.”

MAJA DJURISIC AND RICHIE SAPP, STANFORD The brain’s ability to alter its neuronal connections based on experience is typically halted prior to adulthood due to the the paired-immunoglobulin–like receptor B (PirB) protein; knocking out PirB led to mice having greater plasticity throughout their lives, according to a study published this week (October 15) in Science Translational Medicine. This allowed new, functional synapses to form, and even restored eye sight in animals with so-called “lazy eye.” “There is a lot of interest in the ‘critical period’ of development when the brain is plastic and undergoes a lot of changes and learning,” said Christiaan Levelt, who studies the biology of visual plasticity at the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience in Amsterdam and was not involved in this work. “This study shows that, in an adult animal, you can re-open this critical period window and get enhanced plasticity.”

WIKIMEDIA, GROMBOA phylogenetic analysis of more than 25,000 archaeal gene families found that the integration of bacterial genes into the genome paralleled the pattern of archaeal-specific genes in each of 13 orders of archaea, suggesting that archaeal lineages picked up groups of bacterial genes at the time of their formation. The study was published this week (October 15) in Nature. “It seems like for each major branch of the archaea, the pivotal event that led to the isolation and specialization of each respective clade was the acquisition of a large number of bacterial genes,” said Eugene Koonin, who studies evolutionary genomics at the US National Center for Biotechnology Information. Koonin has collaborated with the study’s authors but was not involved in the present work.

WIKIMEDIA, GROMBOA phylogenetic analysis of more than 25,000 archaeal gene families found that the integration of bacterial genes into the genome paralleled the pattern of archaeal-specific genes in each of 13 orders of archaea, suggesting that archaeal lineages picked up groups of bacterial genes at the time of their formation. The study was published this week (October 15) in Nature. “It seems like for each major branch of the archaea, the pivotal event that led to the isolation and specialization of each respective clade was the acquisition of a large number of bacterial genes,” said Eugene Koonin, who studies evolutionary genomics at the US National Center for Biotechnology Information. Koonin has collaborated with the study’s authors but was not involved in the present work.

Ebola Update

Despite wearing protective gear, two nurses at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas who helped treat the first US Ebola patient have tested ...