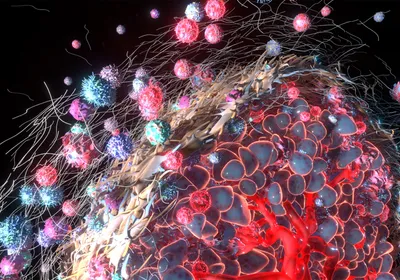

Nanoparticles glow fluorescent green as cells sensitive to drugs produce the capsase enzyme. BRIGHAM AND WOMEN’S HOSPITAL, ASHISH KULKARNIMost methods traditionally used to monitor the effectiveness of a cancer treatment, such as positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, detect decreases in tumor size only after several rounds of therapy. But researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston have now developed a technique that causes drug-transporting nanoparticles to glow with fluorescence as their target cells die, making it possible to visualize the effectiveness of a therapy much sooner than with standard methods. The team described its technique in a mouse study published yesterday (March 28) in PNAS.

Nanoparticles glow fluorescent green as cells sensitive to drugs produce the capsase enzyme. BRIGHAM AND WOMEN’S HOSPITAL, ASHISH KULKARNIMost methods traditionally used to monitor the effectiveness of a cancer treatment, such as positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, detect decreases in tumor size only after several rounds of therapy. But researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston have now developed a technique that causes drug-transporting nanoparticles to glow with fluorescence as their target cells die, making it possible to visualize the effectiveness of a therapy much sooner than with standard methods. The team described its technique in a mouse study published yesterday (March 28) in PNAS.

“Using this approach, the cells light up the moment a cancer drug starts working,” study coauthor Shiladitya Sengupta of Brigham and Women’s said in a statement. “We can determine if a cancer therapy is effective within hours of treatment.”

In the new method, tested in tumor-bearing mice, the researchers used nanoparticles of approximately 100 nanometers in diameter to deliver both a cytotoxic drug and a fluorescent reporter to tumor cells. The fluorescent reporter had been designed to glow only in the presence of capsase—an enzyme produced when cells die, thus producing a visual indicator of a treatment’s success within only a few hours of its administration.

After trialing the method with both a common chemotherapeutic agent, paclitaxel, and an anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy, “we’ve demonstrated that this ...