© MICHELLE KONDRICHReceiving three separate courses of a new class of anticancer immunotherapy agents is not typical for a cancer patient, yet that is what retired Major League Baseball administrator Bill Murray, now 79, endured to treat his melanoma. “When I was told that I might be dying from melanoma, I thought I might as well go for it,” says Murray. In 2011, Murray was given a round of a peptide-based vaccine plus nivolumab (Opdivo), a monoclonal antibody that targets the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) displayed on the surface of T cells, as part of a clinical trial at the Moffitt Cancer Center in Florida. Unfortunately, this two-pronged attack—lasting 12 weeks—didn’t work.

© MICHELLE KONDRICHReceiving three separate courses of a new class of anticancer immunotherapy agents is not typical for a cancer patient, yet that is what retired Major League Baseball administrator Bill Murray, now 79, endured to treat his melanoma. “When I was told that I might be dying from melanoma, I thought I might as well go for it,” says Murray. In 2011, Murray was given a round of a peptide-based vaccine plus nivolumab (Opdivo), a monoclonal antibody that targets the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) displayed on the surface of T cells, as part of a clinical trial at the Moffitt Cancer Center in Florida. Unfortunately, this two-pronged attack—lasting 12 weeks—didn’t work.

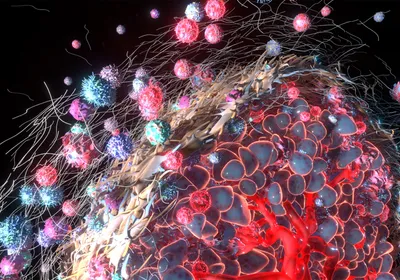

PD-1 is a signaling receptor on activated T cells that functions as an immune checkpoint, tamping down T cell activity when it detects its counterpart, PD-L1, on a tumor cell’s surface. Blocking PD-1 was intended to keep Murray’s T cells actively fighting the cancer. Because his tumors did not completely go away, Murray’s doctor gave him ipilimumab (Yervoy), then a newly approved antibody, which binds cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), also expressed on the same T cells that express PD-1. Ipilimumab also serves as a checkpoint blockade releasing the checkpoint’s break on the immune cells, allowing active T cells to attack cancer. Murray’s tumors began to shrink after 12 weeks of treatment. After several more months, ipilimumab “essentially made his disease disappear,” says Murray’s oncologist ...