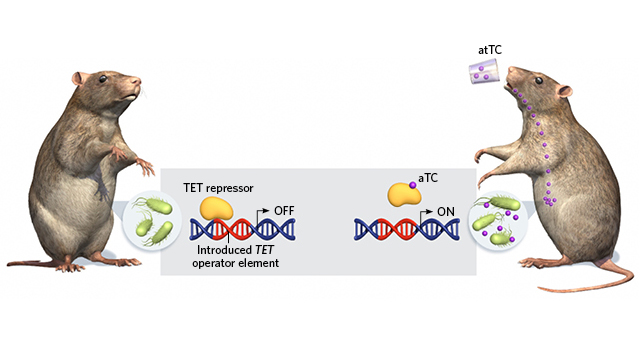

BUG CONTROL: Researchers modified an endogenous Bacteroides promoter sequence to be inducible—it can be turned on or off in mice by adding (right) or omitting (left) anhydrotetracycline (aTC) to the animal’s drinking water. The aTC binds to the TET repressor protein (yellow), thereby preventing its suppression of gene expression. As a proof of principle, the researchers integrated the modified promoter upstream of a sialidase gene in the bacterium’s genome, and showed they could control the enzyme’s activity in mouse intestines.© GEORGE RETSECK

BUG CONTROL: Researchers modified an endogenous Bacteroides promoter sequence to be inducible—it can be turned on or off in mice by adding (right) or omitting (left) anhydrotetracycline (aTC) to the animal’s drinking water. The aTC binds to the TET repressor protein (yellow), thereby preventing its suppression of gene expression. As a proof of principle, the researchers integrated the modified promoter upstream of a sialidase gene in the bacterium’s genome, and showed they could control the enzyme’s activity in mouse intestines.© GEORGE RETSECK

The past decade has seen a surge in microbiome research and, with it, a greater appreciation of the relationships between resident microbes and their hosts. But the focus is shifting, says microbiologist and immunologist Justin Sonnenburg of Stanford University. A major goal of the field, at least in terms of human research, he says, is “to leverage our gut microbes so they can perform tasks,” such as deliver drugs or take physiological measurements.

But engineering gut bacteria is not straightforward, primarily because researchers have relatively little experience with the species that live in and on our bodies, says gastroenterologist Suzanne Devkota of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. “There are 1,001 ways to genetically manipulate E. coli,” she says, “but that’s not particularly useful in ...