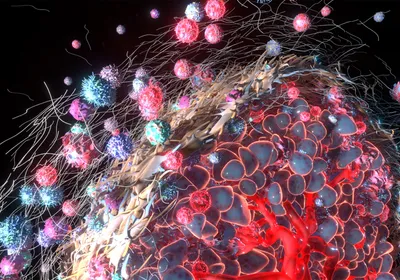

ABOVE: © ISTOCK.COM, SX70

This Saturday (September 11) marks the 20th anniversary of the coordinated terrorist attacks that claimed the lives of almost 3,000 people in New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. On the morning of 9/11, several thousand first responders—police officers, firefighters, paramedics, and emergency medical technicians—arrived at the wreckage of the World Trade Center in New York City, where they encountered plumes of toxic dust, fires that burned unabated for months, unstable wreckage, and otherwise dangerous working conditions.

Almost immediately after the attacks, many first responders began to report health issues, including the so-called World Trade Center cough. And in the two decades since, scientists have documented a number of diseases and mental health disorders among those who helped in rescue and cleanup efforts in the months that followed. According to a recent report released by the Fire Department of the City of New York’s World Trade Center (WTC) ...