FLICKR, ROMAN PAVLYUK

FLICKR, ROMAN PAVLYUK

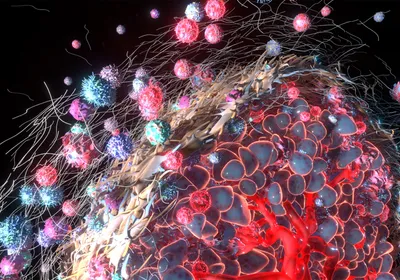

Decades of epidemiological data demonstrate that men have higher overall cancer rates than women. This difference in risk is more than four-fold for some types of cancer, but the reasons for the disparity remain mostly mysterious.

In an investigation of blood samples from more than 1,000 men, scientists at Uppsala University in Sweden and their colleagues found that those with higher rates of chromosome Y loss tended to die younger and were more susceptible to a variety of cancers. Now, some of the same researchers have shown that smoking behavior is strongly linked to the loss of the Y chromosome—a relatively common occurrence. The results, reported today (December 4) in Science, suggest a mechanism for the increased risk of many cancers observed in male smokers ...