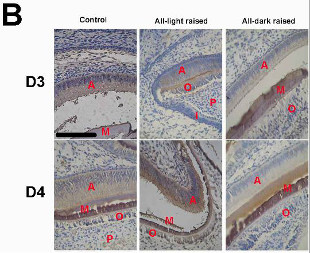

Immunocytochemistry of amelogenins in the first molar tooth germ of mice raised in either night-deprived or daylight-deprived conditions (D3) as well as mice that experienced three-day circadian rhythm derivation followed by one day-night cycle (D4) (40x magnification; scale bar 10μm; A, ameloblast; I, inner enamel epithelium; M, mineralization layer; P, dental papilla cell; O, odontoblast)PLOS ONE, J. TAO ET AL.Melatonin, a hormone found in plants and animals alike, is most often associated with sleep. Secreted by the pineal gland in the human brain, its levels ebb and flow throughout the day, following a circadian rhythm and peaking at nighttime as it alerts the body to the end of the waking day. The hormone has some lesser known effects, too. Namely, in the mouth, where studies in rodents have shown melatonin can do everything from curtail damage caused by periodontitis, a gum disease, to reduce mucositis, the painful inflammation of mucous membranes often caused by cancer treatments.

Immunocytochemistry of amelogenins in the first molar tooth germ of mice raised in either night-deprived or daylight-deprived conditions (D3) as well as mice that experienced three-day circadian rhythm derivation followed by one day-night cycle (D4) (40x magnification; scale bar 10μm; A, ameloblast; I, inner enamel epithelium; M, mineralization layer; P, dental papilla cell; O, odontoblast)PLOS ONE, J. TAO ET AL.Melatonin, a hormone found in plants and animals alike, is most often associated with sleep. Secreted by the pineal gland in the human brain, its levels ebb and flow throughout the day, following a circadian rhythm and peaking at nighttime as it alerts the body to the end of the waking day. The hormone has some lesser known effects, too. Namely, in the mouth, where studies in rodents have shown melatonin can do everything from curtail damage caused by periodontitis, a gum disease, to reduce mucositis, the painful inflammation of mucous membranes often caused by cancer treatments.

In a study published this month (August 5) in PLOS ONE, researchers report evidence to suggest that melatonin is involved in murine tooth development.

Following on a study that identified melatonin receptors in the immature teeth of both mice and humans, scientists at the University of British Columbia, Canada, and the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine sought to explore whether circadian rhythms mediated in part by the hormone may have an effect on dental development and health. To do this, they housed three groups of pregnant mice in environments with normal light/dark cycles, constant light, or constant darkness. The scientists then examined the teeth of mouse pups born to these mothers.

“The effects were dramatic,” said study coauthor William Jia, an associate professor ...