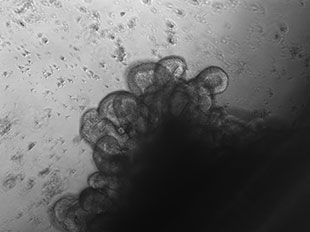

CANCER STEM CELLS IN A DISH: Cells isolated from a patient with metastatic colon cancer grown in organoid (3-D) culture. The organoid shown here recapitulates the crypt-like structures typical of those in the colon tissue of humans.COURTESY OF PIERO DALERBA (COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY), DARIUS M. JOHNSTON AND MICHAEL F. CLARKE (STANFORD UNIVERSITY)For years, cancer researchers have sought to understand why tumors grow back in patients who have successfully undergone chemotherapy and/or radiation. One explanation, proposed in the late 1970s, was the cancer stem cell (CSC) hypothesis, which posits that a small fraction of cancer cells can self-renew indefinitely and give rise to the different cell types in a tumor. The CSC hypothesis can also explain why many cancers are resistant to standard courses of therapy: the drugs don’t affect the stem cell population. If that’s true, then drugs that eradicate CSCs could in theory cure cancer. By purifying CSCs from patient samples, scientists can study these cells in the lab to understand why they persist after cancer treatment.

CANCER STEM CELLS IN A DISH: Cells isolated from a patient with metastatic colon cancer grown in organoid (3-D) culture. The organoid shown here recapitulates the crypt-like structures typical of those in the colon tissue of humans.COURTESY OF PIERO DALERBA (COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY), DARIUS M. JOHNSTON AND MICHAEL F. CLARKE (STANFORD UNIVERSITY)For years, cancer researchers have sought to understand why tumors grow back in patients who have successfully undergone chemotherapy and/or radiation. One explanation, proposed in the late 1970s, was the cancer stem cell (CSC) hypothesis, which posits that a small fraction of cancer cells can self-renew indefinitely and give rise to the different cell types in a tumor. The CSC hypothesis can also explain why many cancers are resistant to standard courses of therapy: the drugs don’t affect the stem cell population. If that’s true, then drugs that eradicate CSCs could in theory cure cancer. By purifying CSCs from patient samples, scientists can study these cells in the lab to understand why they persist after cancer treatment.

Researchers definitively identified CSCs in blood tumors beginning with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in 1997, but the presence of CSCs in solid tumors was hotly debated because experiments using cell-surface markers to demonstrate their presence in solid tumors often yielded inconsistent results. In recent years, however, cells with self-renewing and tumor-initiating properties have been found in all tumor types: glioblastoma, colorectal, breast, pancreatic, and lung cancers. The debate no longer centers around “Do cancer stem cells exist?” but rather, “How many different types of cancer stem cells are there?”

One big barrier to understanding the biology of CSCs is easy access to patient samples; many hospitals freeze tumor sections, but it’s much harder to obtain large numbers of viable cells from thawed tissues than from ...