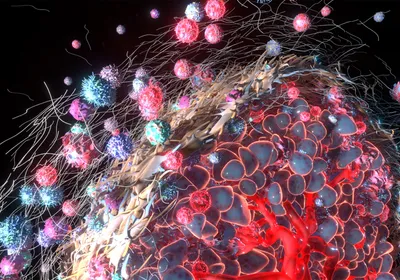

HeLa cells labeled for plasma membrane (red), intracellular midbodies (green) and nuclei (blue). CHUN-TING CHEN AND STEPHAN DOXSEY

HeLa cells labeled for plasma membrane (red), intracellular midbodies (green) and nuclei (blue). CHUN-TING CHEN AND STEPHAN DOXSEY

Midbodies, once considered the rubbish of cell division, might have a function beyond their role in getting daughter cells to separate. Researchers show in today's Nature Cell Biology that stem cells and cancer cells collect used midbodies, whereas differentiated cells digest the organelle through autophagy.

“The midbody is now emerging as a signaling center or an organizer for things that may have to do with the stemness of cells,” said Andreas Ettinger, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden, Germany, who was not involved in this study.

During cytokinesis, a single midbody forms as part of a bridge between daughter cells, and its proteins participate in abscission, the final cut that severs the two cells. Discovered ...