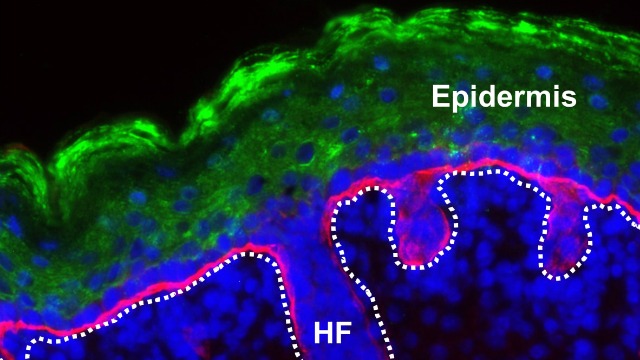

An immunofluorescence image of one of the engineered skin graftsXIAOYANG WU ET AL.In a proof of concept study, researchers have used a gene-edited skin graft to treat diabetes in mice, they reported yesterday (August 3) in Cell Stem Cell.

An immunofluorescence image of one of the engineered skin graftsXIAOYANG WU ET AL.In a proof of concept study, researchers have used a gene-edited skin graft to treat diabetes in mice, they reported yesterday (August 3) in Cell Stem Cell.

The graft is grown from mouse stem cells engineered by CRISPR to produce the GLP-1 enzyme, which stimulates insulin release. Obese and diabetic mice treated with the patch did not display signs of diabetes and gained less weight when fed a high-fat diet.

The study is “pretty exciting” says David Taylor, a structural biologist at the University of Texas at Austin, who was not involved in the work. In contrast to gene therapies that aim to correct the mutation causing a disease, this would be “like another way of taking a drug orally—in this case it’s on your skin,” he says.

The stem cells used in the graft had the gene for GLP-1 inserted next to a promoter activated by the antibiotic doxycycline. While GLP-1 ...