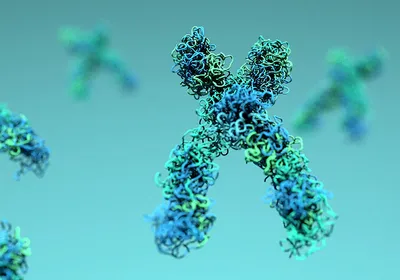

DNA methylation

Trending

Universe 25 Experiment

A series of rodent experiments showed that even with abundant food and water, personal space is essential to prevent societal collapse, but Universe 25's relevance to humans remains disputed.

The Federal Government’s Research Innovation Lifeline Has Gone Dark

Congressional inaction has led to the expiration of the federal government’s SBIR/STTR program, cutting off a biotechnology lifeline.

What Are Giant Viruses, and Are They Dangerous?

Lurking in the vast expanse of the ocean and buried deep in the Siberian permafrost, there are giants—not blue whales and mammoths, but giant viruses.

New “Kill Test” Could Help Screen Better Antibiotics

A new single cell-based screening tool evaluates how well antibiotics kill bacteria and may help researchers determine which drugs perform best in patients.

Multimedia

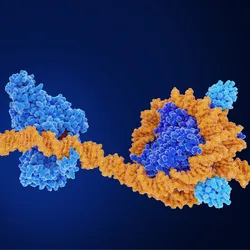

Redefining Immunology Through Advanced Technologies

In this webinar, scientists will discuss innovations that are unlocking new insights into immunity.

Ensuring Regulatory Compliance in AAV Manufacturing with Analytical Ultracentrifugation

In this webinar, Magdalena Pacewicz will highlight how to use AUC to characterize AAVs as part of ensuring regulatory compliance.