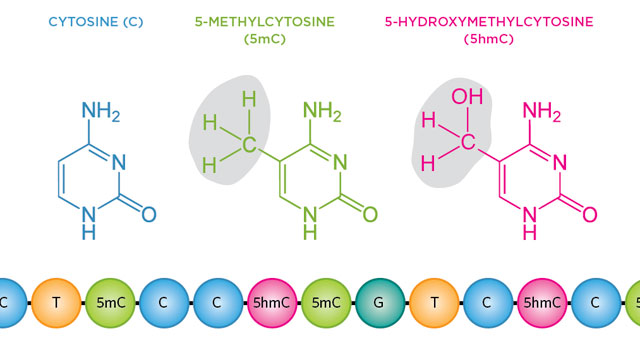

The DNA base cytosine has a tendency to play dress-up, gaining and shedding chemical modifications. For more than 40 years, scientists have known that methyl groups attached to cytosine’s fifth carbon atom can alter gene expression. These epigenetically marked bases, called 5-methylcytosines (5mCs), help to determine how hundreds of cell types in the human body differentiate and maintain their identities, despite having the same genetic backgrounds.

Recently, researchers have rediscovered a mostly ignored epigenetic variant that results when a methyl group on a cytosine takes on a hydroxyl group to form 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC). The favored method for detecting methylation is bisulfite sequencing, which converts unmodified cytosine to uracil, which then reads as thymine following PCR amplification. Modified cytosines continue to read as cytosines. This technique ...