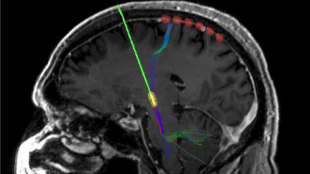

During surgery to implant a permanent DBS device (green with yellow tip) in the brain of a Parkinson’s patient, six recording electrodes (red) were temporarily placed on the surface of the brain. COURTESY OF CORALIE DE HEMPTINNEStimulate the brain of a patient suffering from Parkinson’s disease (PD) via a surgically implanted electrode and there’s no mistaking the results: the person’s slow movement, tremor, and/or rigidity—common symptoms of the neurodegenerative disorder—all but disappear immediately. When the device is turned off, the motor symptoms return in full force. But how deep-brain stimulation (DBS) effects such changes has been unclear.

During surgery to implant a permanent DBS device (green with yellow tip) in the brain of a Parkinson’s patient, six recording electrodes (red) were temporarily placed on the surface of the brain. COURTESY OF CORALIE DE HEMPTINNEStimulate the brain of a patient suffering from Parkinson’s disease (PD) via a surgically implanted electrode and there’s no mistaking the results: the person’s slow movement, tremor, and/or rigidity—common symptoms of the neurodegenerative disorder—all but disappear immediately. When the device is turned off, the motor symptoms return in full force. But how deep-brain stimulation (DBS) effects such changes has been unclear.

In a study published yesterday (April 13) in Nature Neuroscience, researchers at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), uncovered evidence to suggest that DBS works by reducing the overly synchronized activity of the motor cortex, which controls the body’s skeletal muscles.

Two years ago, UCSF neurosurgeon Philip Starr, postdoc Coralie de Hemptinne, and their colleagues had identified extremely synchronized neural activity in the cortex as a common factor in the Parkinson’s brain. For the new study, the researchers temporarily placed a strip of six recording electrodes over the motor cortex of 23 Parkinson’s patients during surgery to implant a permanent DBS electrode. Over the course of the six-hour surgery, during which patients are awoken to ensure the proper placement of the DBS electrode, “we ...