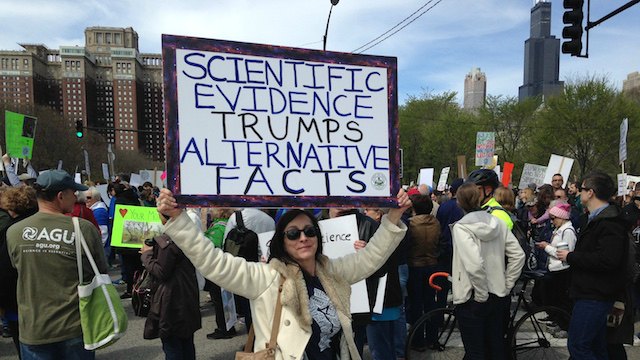

Peggy Mikros, a caterer, at the March for Science in ChicagoKERRY GRENSThe past 12 months have seen no shortage of science scandals, policy upheaval, and publishing turmoil (so we gave them their own dedicated end-of-year summaries). Yet the show of solidarity within the scientific community this year could warm the heart of even the sourest Grinch. Scientists rallied together by the tens of thousands to advocate for evidence-based policymaking during the March for Science; they opened up their labs to researchers affected by hurricanes and travel bans; and they protested against sexual harassment by colleagues and inaction by institutions.

Peggy Mikros, a caterer, at the March for Science in ChicagoKERRY GRENSThe past 12 months have seen no shortage of science scandals, policy upheaval, and publishing turmoil (so we gave them their own dedicated end-of-year summaries). Yet the show of solidarity within the scientific community this year could warm the heart of even the sourest Grinch. Scientists rallied together by the tens of thousands to advocate for evidence-based policymaking during the March for Science; they opened up their labs to researchers affected by hurricanes and travel bans; and they protested against sexual harassment by colleagues and inaction by institutions.

Here are stories that have made 2017 a year to remember.

From the rainy US capital to sunny Chicago to brisk Berlin, scientists and their supporters took to the streets across the globe for the largest science advocacy event in history. While billed as a nonpartisan gathering, the hand-drawn signs people made spoke to an overwhelming concern about President Donald Trump’s policies.

For many researchers, it was their first time advocating for their field. “I’ve never protested before, ever,” Karl Klose, a microbiologist at the University of Texas, San Antonio, told The Scientist at the march in Washington, D.C. But he was motivated to do so after Trump’s proposed budget included major slashes to funding for the National Institutes of Health. “It was kind of ...