ABOVE: © scott leighton

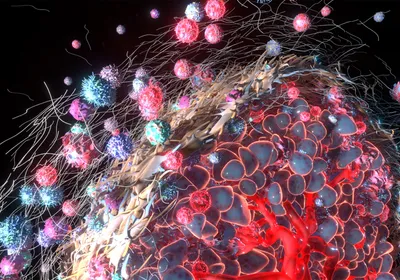

Researchers are beginning to understand that not only can exercise improve cancer patients’ overall wellbeing during treatment, but it may also fight the cancer itself. Experiments on cultured cells and in mice hint at some of the mechanisms that may be involved in these direct and indirect effects.

Exercising muscles release multiple compounds known as myokines. Several of these have been shown to affect cancer cell proliferation in culture, and some, including interleukin-6, slow tumor growth in mice.

Exercise stimulates an increase in levels of the stress hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine, which can both act directly on tumors and stimulate immune cells to enter the bloodstream.

Epinephrine also stimulates natural killer cells to enter circulation.

In mice, interleukin-6 appears to direct natural killer cells to home in on tumors.

In lab-grown cells and in mice, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and some myokines hinder tumor growth and metastasis.

Read ...