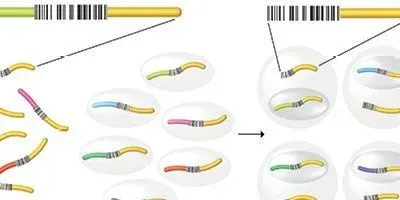

SINGLE-CELL SCREEN: A library of guide RNAs—each targeting a unique gene for CRISPR-based interference and carrying a unique barcode sequence—is introduced into a population of cells at a concentration that results in one guide RNA entering one cell, on average. Individual cells are then sorted into droplets bearing uniquely barcoded polyT primers, which are used to extract the cell’s mRNA. Sequencing the RNA then reveals both the introduced genetic mutations—determined by the guide RNA—and the transcriptional effect of that perturbation—determined by the collection of mRNAs bearing the cell-specific barcode (from the polyT primer).© GEORGE RETSECK

SINGLE-CELL SCREEN: A library of guide RNAs—each targeting a unique gene for CRISPR-based interference and carrying a unique barcode sequence—is introduced into a population of cells at a concentration that results in one guide RNA entering one cell, on average. Individual cells are then sorted into droplets bearing uniquely barcoded polyT primers, which are used to extract the cell’s mRNA. Sequencing the RNA then reveals both the introduced genetic mutations—determined by the guide RNA—and the transcriptional effect of that perturbation—determined by the collection of mRNAs bearing the cell-specific barcode (from the polyT primer).© GEORGE RETSECK

Determining how the genes in a cell affect its function is the overarching objective of molecular genetic studies. But most genotype-phenotype screens are limited by the number of genetic perturbations that can be feasibly measured in one experiment. In short, the more genetic disruptions examined, the more costly and time-consuming the experiments become.

Indeed, says Trey Ideker of the University of California, San Diego, very few large-scale genotype-phenotype screens have been performed, and those that have were mammoth undertakings. Now, thanks to two highly similar techniques—one called Perturb-Seq, developed by Aviv Regev of the Broad Institute and colleagues, and another, designed by Ido Amit of the Weizmann Institute in Israel and colleagues, called CRISP-Seq—it is possible to study numerous genetic manipulations, individually or combined, in ...