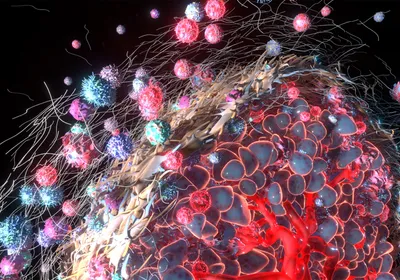

© DIM TIK/SHUTTERSTOCK.COMA decade ago, scientists studying the human genome found 1,447 copy number variable regions, covering a whopping 12 percent of the genome (Nature, 444:444-54, 2006). Ranging in size from 1 kilobase to many megabases, the number of repetitive DNA sequences scattered throughout the human genome can expand and contract like an accordion as cells divide. Extra—or too few—copies of these repeats, known as copy number variations (CNVs), can explain inherited diseases or, when the copy number change occurs sporadically in somatic cells, can result in cancer. Today, a growing number of scientists are making links between CNVs, health, and disease.

© DIM TIK/SHUTTERSTOCK.COMA decade ago, scientists studying the human genome found 1,447 copy number variable regions, covering a whopping 12 percent of the genome (Nature, 444:444-54, 2006). Ranging in size from 1 kilobase to many megabases, the number of repetitive DNA sequences scattered throughout the human genome can expand and contract like an accordion as cells divide. Extra—or too few—copies of these repeats, known as copy number variations (CNVs), can explain inherited diseases or, when the copy number change occurs sporadically in somatic cells, can result in cancer. Today, a growing number of scientists are making links between CNVs, health, and disease.

But measuring CNVs in cells from an individual can be tricky. For a number of years, researchers relied on fluorescently tagged microarray probes that attached to sections of genes; locations where the probes fluoresced more or less brightly than in an average genome suggested duplications or deletions of repeats within the CNV region, but the resolution was generally low. Throughout the early 2000s, researchers moved toward using higher-resolution microarrays to detect CNVs, and commercial kits became available that provided the probes needed for these assays. More recently, the advent of high-throughput genome sequencing has offered a new way to detect and quantify, or “call,” CNVs.

“This seems to be the next wave in CNV calling,” says computational biologist Dan Levy of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. ...